The Death of Jordan Neely

On Monday, May 1, Jordan Neely was choked to death on the northbound F train “after he threatened straphangers,” according to police. The man who put him in a chokehold was Daniel Penny, a 24-year-old ex-Marine. Other passengers assisted Penny, but because he was white and Neely was black, the incident became fodder for the usual rushes to judgment, with every partisan side slotting Neely into their preferred narratives:

— He was a mentally ill man with a record of violent assaults.

— He was a beloved street entertainer suffering from homelessness1 who was killed because he was hungry and “making people uncomfortable.”

Most of those commenting either had a cursory understanding of the facts or were ignoring them.

Here is Roxanne Gay in the New York Times.

Was he making people uncomfortable? I’m sure he was. But his were the words of a man in pain. He did not physically harm anyone. And the consequence for causing discomfort isn’t death unless, of course, it is.

“Making People Uncomfortable Can Now Get You Killed”

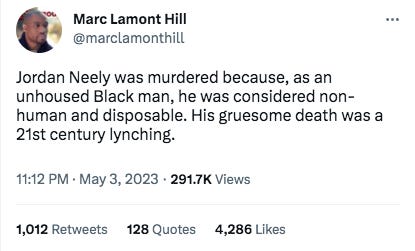

Journalist Marc Lamont Hill was one of many who called Neely’s death a lynching.

What happened?

At around 2:25 pm on Monday, May 1, Neely boarded the northbound F train at 2nd Avenue. He began screaming at the passengers that he was hungry and thirsty and didn’t care anymore. He then threw down his jacket, at which point people started moving away from him. This is the “uncomfortable” that Roxanne Gay was talking about. I’m a long-time subway rider and I’ve encountered many “uncomfortable” people, and I rarely move away. For a New Yorker to move away, their threat meter has to spike.

According to Juan Alberto Vasquez—a freelance journalist who took a video of part of the choking—Neely was acting aggressively and had said, “I’m tired already. I don’t care if I go to jail and get locked up. I’m ready to die.” Depending on how it’s said, “I’m ready to die” can sound either tragic or threatening. Vasquez interpreted it as the latter.

To me, when Jordan throws his jacket, it is a way of saying: “There could be an act of violence here,” because those things do happen all the time, because just a year ago, there was a guy who went in and shot a lot of people on the train. And obviously, the marine, in the end, went too far. But the police also went too far in not arriving on time.

At some point during the short ride between stations, after the jacket had been thrown, Daniel Penny, a 24-year-old ex-marine, grabbed Neely in a chokehold and wrestled him to the ground. Two other men joined in to hold down Neely’s hands and legs. When they arrived at Broadway-Lafayette station, most passengers rushed out of the subway car.

During this period, five 911 calls (emergency services) were made, starting at 2:26 pm. The first call reported a physical fight, another call said someone was threatening riders, a third caller said someone had a knife or a gun. It’s unclear whether the calls came before or during the time Neely was being wrestled to the ground and choked. The report of a weapon by one caller might have been honest confusion, but it also might have been standard tale-telling escalation. A New Yorker knows the cops are more likely to come if they are told there’s a weapon. Five 911 calls is a pretty big deal. New Yorkers don’t call the cops for nothing. In fifty years of living in New York, I’ve called the police twice.

The crowd alerted the train conductor that something was wrong, and he kept the train doors open. The ride between the two stations had taken less than two minutes.

Vasquez’s 3:48-minute-long video begins after Neely is already being held down and the train is stopped in the station. Penny has him in a chokehold, and another man is holding Neely’s arms. Neely struggles for the first two minutes of the video (in an interview, Vasquez describes “his attempts to escape”), then seems to stop moving at the 2:00-minute mark. Eighteen seconds later, at the 2:18-mark, another passenger warns that the choking may kill Neely. It’s hard to tell, but it seems Penny is no longer holding Neely in a tight grip. The black man who is helping by holding Neely’s arm reassures, “It’s cool,” and at minute 2:32, “he’s not squeezing no more.” At minute 2:50, the men get up and put Neely into a recovery position on his side. At this point, it’s probably already too late for Neely. (Note: The times given in this paragraph are minutes into the video. The estimated clock time is below.)

Rough timeline

2:25 pm (approximately) - Neely enters the train at 2nd Avenue.

2:26 pm - The first 911 call.

2:29 pm - Passenger warns Neely could die. Reassured he’s not being choked.

2:30 pm (approximately) - Men stop holding Neely.

2:32 pm (approximately) - Police arrive.

2:46 pm - Fire department paramedics arrive.

[EDIT May 11: A key time is police arrival. The New York Post quotes Mayor Adams as saying the police arrived within 6 minutes of the first call. If that’s not true, that might mean that Neely was held down for longer than 3 to 5 minutes, as the current timeline and below paragraph argue.]

One bit of misinformation that crept into Twitter debates was a claim that Penny held Neely in a chokehold for 15 minutes. The video shows this was far from the case. Combined with the testimony of Vasquez, it seems that Neely was held down for between 3 and 5 minutes.2 It’s unclear whether his throat was being compressed during that whole time, but it seems unlikely. Whatever the amount was, it was too much. (A chokehold is supposed to put pressure on the carotid artery and cut off the blood to the brain, leading to unconsciousness in less than 10 seconds. Care is supposed to be taken not to crush the windpipe.)

The police arrived at around 2:32 pm and unsuccessfully attempted to resuscitate Neely. The medical examiner later declared that the death was a homicide and that Neely had died from “compression of neck.”

Who was Jordan Neely?

Neely suffered from PTSD, schizophrenia, and depression. He’d started with brighter dreams, of course, as most of us do. In his high school days, he was famous for imitating Michael Jackson. He later turned this into a job of sorts, busking (entertaining for money) in subway stations and on trains. When he was 14, his mother was strangled to death by her boyfriend. Neely was forced to testify at the murder trial (which took place when he was 19), confronting the boyfriend, who acted as his own lawyer, an impossibly traumatic experience. After his mother’s death, his life went steadily downhill. Busking is a hard way to make a living, and Neely’s mental condition deteriorated.

My sister Christie was murdered in ’07 and after that, [Jordan Neely] has never been the same

By the time he had his fatal encounter, Neely was on what social workers called their “Top 50” list, comprised of people most in need of help. He was using K2, a dangerous synthetic version of marijuana. A mental health outreach team took him to Bellevue Hospital in 2020, but he only stayed a week.

Neely racked up a lengthy criminal record, with more than 40 arrests, some of them for violent assaults. In 2015, he served four months in jail for attempting to drag a 7-year-old girl down a street in Inwood. In 2019, he attacked a 68-year-old man, Filemon Castillo Baltazar, at the West 4th Street subway station. “Out of nowhere, he punched me in the face.” In 2021, he was arrested for assaulting a 67-year-old woman with another punch to the face. She suffered a broken nose and orbital bone. Neely served 15 months in jail awaiting trial and gave a guilty plea in return for being put in a probation program. As part of the program, he was required to live at a treatment facility and stay off drugs.

“This is a wonderful opportunity to turn things around, and we’re glad to give it to you,” Mary Weisgerber, a prosecutor, said.

“Thank you so much,” Mr. Neely replied.

Thirteen days later, he left the program. An arrest warrant was issued in February 2023. The warrant was still outstanding when he entered the F train car.

Outreach workers continued to have encounters with Neely after February. (Social workers do not normally check to see if there are any outstanding warrants on the people they are trying to help.)

The following week [in April], an outreach worker saw him in Coney Island and noted that he was aggressive and incoherent. “He could be a harm to others or himself if left untreated,” the worker wrote.

Neely’s crimes are not evidence that he deserved to die, not at all. It is clear, however, that Neely was a troubled and sometimes violent young man. If the subway passengers sensed violence that day, it’s because it was there. And it’s understandable that subway passengers would be concerned about subway violence.

Since March 2020, at least 27 people have been murdered on the New York subway. Many of these homicides have been committed by mentally-ill people with a history of aggressive behavior at stations. Last year, in an incident that garnered international headlines, a New York resident named Michelle Go was shoved into a train by a man with a history of mental illness.

— Lee Fang

And?

Neely’s death was a tragedy. As Lee Fang puts it, “The system failed Jordan Neely.” It’s wrong to frame Neely’s death as a result of racism. There is no evidence that Penny was motivated by anything but a desire to restrain a man he believed was dangerous, assisted by other passengers. This doesn’t mean his actions were justified. The Manhattan District Attorney will decide whether prosecution is appropriate, but clearly, what happened was not what Penny intended.

Observers have rightly pointed to Neely’s homelessness as a cause of his desperate state of mind that led him to scream for food and water in that subway car, but they ignore that just a few months earlier, he had been offered a bed in a treatment residence. He’d had a home and he’d chosen to leave. His reasons probably stemmed from drug addiction and mental instability. As a society, we offer forgotten men like Neely too little help, but what do we do when that help is offered and refused?

It’s also impossible not to notice that Neely’s tragic death only garnered so much attention because he was choked on video and by a white man. In 2021, 488 people were murdered in New York City. Most of them, 359, were black, and most of their murderers were also black. Nobody called their deaths “lynchings.” Not much was said about them at all.

Sources

“What We Know About Jordan Neely’s Killing,” New York Times

“How Two Men’s Disparate Paths Crossed in a Killing on the F Train,” New York Times

“911 flooded with calls, including reports of a gun, while Jordan Neely was fatally choked on train: cops,” New York Post

“I Wasn’t Thinking That Anybody Was Going to Die,” interview with Vasquez, New York Magazine

“The Outrage Over Jordan Neely’s Killing Isn’t Going Away The man who choked him to death has been identified, but it’s not clear if he’ll face charges,” New York Magazine

“911 timeline moments before Marine vet put Jordan Neely in chokehold on NYC subway,” Fox News

“Criminal charges weighed against Marine in chokehold death of Jordan Neely as NYPD and Manhattan DA confer,” The Daily News

“Voices Politicizing NYC Subway Death Opposed Mayor’s Plan for Severe Mentally Ill,” Lee Fang

A new trend in social justice language is replacing “homeless person” or “the homeless” with “people suffering from homelessness.” The rationale seems to be that the person should not be maligned because of their lack of a home. They are not a “homeless person,” they are a person experiencing a temporary condition that in no way impacts on their worth as a human. The new phrase has led to zero decrease in the number of people suffering from homelessness.

The chokehold began after the train had left the 2nd Avenue station. The ride took less than 2 minutes. The 3-minute 48-second video begins approximately a minute after the train had stopped at the Broadway-Lafayette station, but the chokehold has ended by the 2:30 mark (if not sooner).

good exposition of the story, thanks for this. What's sad to me is that they want to turn this into another George Floyd, their buttons are stuck on racism.

It takes some effort these days to find people who care more about what's true than what their side is supposed to believe, but it's doable. Thank you for being one of them.