The New York Times isn't pro-Nazi

On Sunday, December 18, the New York Times made a crossword puzzle that sent people ballistic. Instead of an array of clever and annoying word clues,1 some observers saw a swastika.

Like many, Meghan McCain was upset that it was posted on the first night of Hanukkah (as if it somehow would have been not quite as bad to post a swastika on other nights).

The “controversy” was covered widely in the media (Fox News, Newsweek, TMZ).

And it’s all nonsense. Full throttle 30-cards-shy-of-a-full-deck bonkerstown. The liberal New York Times, in the heart of multi-ethnic New York City (about 18% Jewish), decided to deliberately put a white supremacist symbol into their crossword puzzle because…um, to troll Israel? This is madness.

Responding to the controversy, Jordan Cohen, director of communications at the Times, said “This is a common crossword design: Many open grids in crosswords have a similar spiral pattern because of the rules around rotational symmetry and black squares.” Unfortunately, a symmetrical spiral pattern can sometimes look a bit like a swastika. A bit.

The puzzle was created by Ryan McCarty, a positivity consultant and word maven who’d previously made 22 New York Times crossword puzzles, although this was his first Sunday puzzle.

Thrilled to have my first Sunday puzzle in The Times! This grid features one of my favorite open middles that I’ve made as it pulls from a variety of subject areas. I had originally tried to make it work in a 15x15 grid but then decided to expand the grid out to a Sunday-size puzzle with a fun whirlpool shape. Hope you enjoy!

WORDPLAY, THE CROSSWORD COLUMN

Could McCarty, the upbeat co-author of “Build a Culture of Good,” be a secret Nazi? I guess it’s possible in the same sense that it’s possible I’m a Stalinist deep-cover agent. (Не волнуйся, я не такой.) His biography on Amazon does reveal the disturbing news that he listens to NPR but I think we can forgive him.

Ryan McCarty has always had a passion for making the world a better place. Ryan's wife and two daughters teamed up with the culture zealot to start a church, build a school in Africa and launch an after-school network that exists across states and even countries. Although Ryan would like to be an old school hip hop star, he spends his spare time listening to NPR and watching Antiques Roadshow while smoking a pipe.

What about his editor, Will Shortz? He’s been a lifetime puzzle dude and the puzzle master on NPR’s Weekend Edition Sunday since 1987. He’s been working at the Times since 1993. He has no ties to Nazism. (Why do I even have to type those words?!?)

So, no, there is no rational world in which those two men, long-time crossword creator and super long-time crossword editor, would deliberately put a swastika into the paper.

“Yeah, but I can see it right there in front of me!”

Sure you can, and your eyes are lying to you, or rather, your brain is.

If I could possess one superpower, it would be the ability to convince people that their understanding of the world is far far more warped by cognitive biases than they think it is. We don’t see the world as it is, we see the world as our brain interprets it, and our brain is a really cool but only semi-accurate tool.

For starters, our brains are pattern seeing machines. As Scientific American put it, they are “wired to find meaning.” This incredibly useful ability allows us to discern important secrets behind random bits of data. (That grass on the savannah is moving, there’s probably a lion there ready to pounce!) Unfortunately, we often get false positives. (It was just the wind.) The evolutionary advantage in sometimes detecting a lion in the grass makes up for often thinking there was one lurking when there actually wasn’t—being not dead that one time is worth being needlessly stressed all those other times—but the downside to all this pattern seeing is it sometimes leads us to create elaborate but false stories based on random data.

The cognitive bias that leads to the swastika illusion is called “pareidolia,” the tendency of humans to see unintended meaning in images. This has often caused us to see things that weren’t there, like Jesus on toast,2 faces on the Moon, or canals on Mars. In fact, a whole set of theories grew up that Martian canals transported water from melting ice caps for an advanced but dying civilization. Sadly for science fiction writers, better telescopes in the 20th century showed that the Martian canals had been an optical illusion.

The artist Giuseppe Arcimboldo (1526-1593) took advantage of pareidolia in his paintings. Here’s a craggy-faced rich merchant.

But look closer and see fish, chickens, and books.

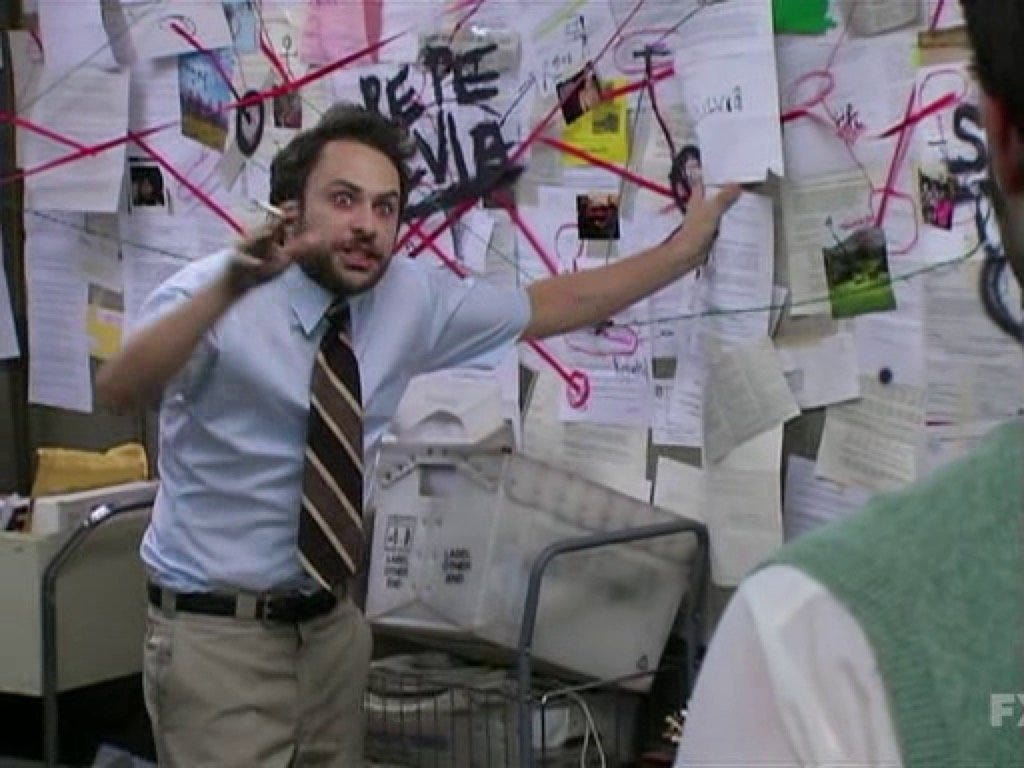

And yet you still see that damn swastika. Part of that is because once you see a pattern it’s almost impossible to unsee it. That pattern our brain has drawn for us becomes reality. “It’s right there in front of me!” I drew a different version, below—much less like a swastika—but you’re probably still detecting the Nazi symbol because your brain already “knows” it’s there.

Look for them and it’s easy to see swastikas in other innocuous designs (someone else made this image, but those were the tiles in my bathroom growing up).

And this seeing evil signs and symbols isn’t new. There is ongoing controversy over the classic “ok” sign because a few right-wing trolls have used it to signal “white power.” (Read about that here.) People on the left are often accused of seeing racism where it wasn’t. (“Why did you ask where she was from? Assuming someone isn’t from here is a racist dog whistle!”) Some on the right claim that calling out a cheerful “Happy Holidays” is proof of a “War on Christmas.” And just last year, quite a few folks claimed to see Nazi symbolism in the shape of the CPAC stage.

And despite all I’ve said, you still see the swastika.

All I can do is say, yes, I‘m sure you see it, but it’s still not there. And no, I’m not gaslighting you. It’s your brain that’s doing that, playing tricks on you as brains often do.

Remember “The Dress” bruhaha? Back in 2015, a dress posted on Facebook tore the Internet apart.

See that blue and black dress? In one study, 30 percent of viewers saw it as white and gold. Crazy, right? Except I’m one of the 30 percent. No matter how hard I try, I keep seeing white and gold. I know it’s not, I know my brain is lying to me, and yet there it is, white and gold. (Wikipedia has a nice page on the whole dress mess.)

So Ryan McCarty and Will Shortz, two liberal NPR fans, didn’t get together and plan out a swastika-themed puzzle. McCarty just used a classic swirl look for a crossword that inevitably will sometimes look a very little bit like a swastika. Your brain will then do the rest.

Some critics have said, “well maybe it wasn’t intentional, but they should have caught it and fixed it.” I guess one could make that case, but then you’d have to exclude a whole swathe of shapes that might in somebody’s mind resemble an evil symbol. None of this will do anything to fight real antisemitism, which has been on the rise over the last few years. My Jewish grandfather didn’t flee Nazi Germany in 1938 because he feared crosswords, he did so because he didn’t want to be beaten or killed by Nazi thugs. Let’s keep our eye on real threats, not imaginary ones.

Full disclosure: I’m bad at crosswords.

Good piece, except that dress is clearly white and gold, you weirdo.

I'm reminded of one of Terry Pratchett's Discworld books where vampires try to train themselves not to be bothered by a cross, since it's merely a simple shape. They repeatedly remind themselves that different simple shapes have meaning to various religions, and go through many examples. Unfortunately, it eventually backfires on them, since they now associate all sorts of shapes with various religions, so they end up being bothered by almost every simple shape.

There's something of that flavor here, inverted - i.e. not (evil vampire) / (good cross) but (good liberal) / (evil swastika). A good person is supposed to be so attuned to the evil of the symbol, that it showing up anywhere, even by accident, is deemed to cause emotional distress. That does have an internal logic of a sort, with the extreme importance often invested in taboo symbols.