Supreme Court Blues

The big Supreme Court rulings have come down, and people are furious, thrilled, depressed, and smug. And my reaction is to feel…lonely.

Looking at my Facebook feed—my real-life acquaintance circle—I see boiling wrath at SCOTUS’s decisions, but I don’t feel the same. I find the court’s rulings understandable, even reasonable. This disconnect makes me feel an exile among my own people.

Affirmative Action

Portraying the Court’s ruling as a victory for white supremacy is odd (not least because one of the Court’s two black justices voted for the decision).

Progressives ignore that Asians were at the heart of Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard. The plaintiffs were arguing that Asian students had been discriminated against in admissions. Not one of the many memes I saw on my Facebook timeline mentioned Asian people. Zero. To not ever mention Asians seems, well, kinda racist.

These admissions policies at Harvard (and at the University of North Carolina, also part of the suit) seem clear violations of both the 14th Amendment's Equal Protection Clause and Title VI of the Civil Rights Act, which prohibit racial discrimination.

In the past, the courts have ruled that very limited racial discrimination can be allowed if it serves an essential purpose, in this case, giving black kids who had already been discriminated against during the deeply racist post-Civil War years a necessary amount of help. It was a way to compensate for the horrors of slavery and Jim Crow.

The Court, in ruling against affirmative action, was arguing that using racial discrimination to fight past racism was no longer a “compelling governmental interest.”

And at Harvard and other elite schools, the anti-Asian discrimination had been blatant and ugly. I understand concerns that without affirmative action, black students would lose out, but why is there no concern about the methods used? Did those who disagreed with the Court’s decision think that discrimination against Asians was ok? Or were they just pretending it didn’t happen?

Harvard consistently rated Asian-American applicants lower than others on traits like “positive personality,” likability, courage, kindness and being “widely respected,” according to an analysis of more than 160,000 student records filed Friday by a group representing Asian-American students in a lawsuit against the university.

Asian-Americans scored higher than applicants of any other racial or ethnic group on admissions measures like test scores, grades and extracurricular activities, according to the analysis commissioned by a group that opposes all race-based admissions criteria. But the students’ personal ratings significantly dragged down their chances of being admitted, the analysis found.

“Harvard Rated Asian-American Applicants Lower on Personality Traits, Suit Says,” New York Times (June 15, 2018)

These ratings implied that Asians were shunted aside because they were less likable than other students, feeding into the nasty stereotype of Asian students as humorless grinds. About half of my students are Asian, mostly from China, and I can assure you that they smile, joke, and are just as charming as all my other students.

Moreover, while Harvard’s admissions policies helped to make their school look more diverse, they did little to help the poor black kids who were the most likely to carry the burdens of discrimination. Rather than boost opportunities for left-behind black Americans, they recruited kids from middle-class (often immigrant) backgrounds. There’s nothing wrong with immigrant kids getting a seat at Harvard, but favoring them does nothing for the main victims of America’s history of racism.

Most reporting on the subject—including my own, as well as a story in the Harvard Crimson—shows that descendants of slaves are relatively underrepresented among Black students at Harvard, compared with students from upwardly mobile Black immigrant families.

”Why the Champions of Affirmative Action Had to Leave Asian Americans Behind,” New Yorker (June 30, 2023)

The Ivies discourage attempts to reveal that their affirmative action programs aren’t helping those most in need of help.

For years, there’s been a move among Harvard students and faculty who are descended from people held in slavery in the United States prior to the Civil War to get the university to say how many of its Black students are Generational African-Americans as opposed to descendants of recent immigrants from Africa and the Caribbean. The university keeps refusing to do this, again because the priority is to avoid the “bad look,” not to achieve any particular social justice goal.

“19 thoughts on affirmative action,” Matthew Yglesias (June 29, 2023)

The anger over the Court’s ruling also ignores that it will affect relatively few students. Affirmative action is only a factor in hyper-selective schools. Most colleges accept most students, and the Ivies are a tiny sliver of the educational pie.

For most black students, the main barrier to entry for a college education is not Harvard’s rigid standards but rather a lack of money and academic preparedness. Affirmative action does nothing to eliminate those problems.

The effect of race-conscious admissions was always limited to a relatively small number of students. For the vast majority, these schools are not an option — academically or financially.

”The ‘Unseen’ Students in the Affirmative Action Debate,” New York Times (July 1, 2023)

The Harvard case was about apportioning seats at the elite table. For most Americans of every race, all those seats are forever out of reach.

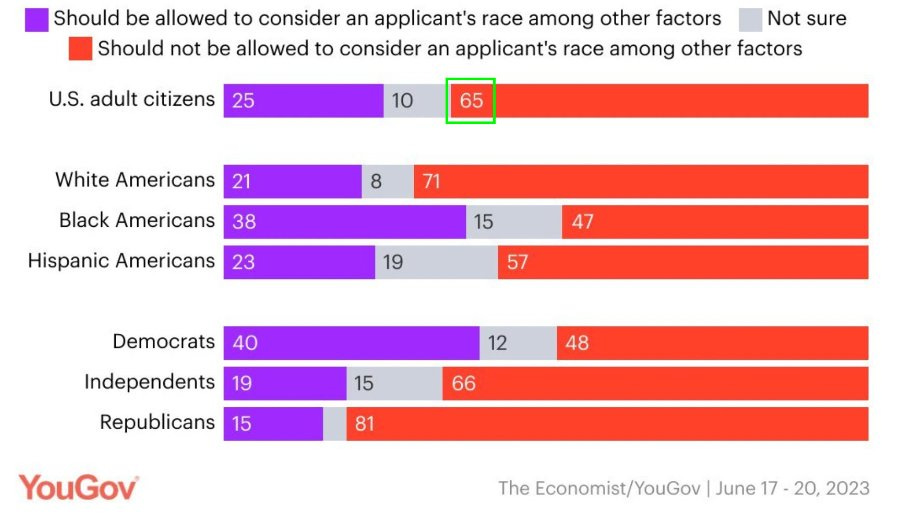

Finally, the Court’s decision was in tune with the country. Most Americans oppose using race as a factor in college admissions. This is something my progressive friend circle doesn’t seem to realize. They feel they have justice on their side and either don’t know or don’t care that most Americans disagree.

These are just polls, but in 2020, California, which overwhelmingly supported Biden in the presidential election, voted down Proposition 16, which would have restored affirmative action, even though supporters outspent opponents 19 to 1. The “no” vote totaled 57%.

Valerie Contreras, a crane operator, is a proud union member and civic leader in Wilmington, where half the voters were against the referendum. She had little use for the affirmative action campaign.

“It was ridiculous all the racially loaded terms Democrats used,” she said. “It was a distraction from the issues that affect our lives.”

“The Failed Affirmative Action Campaign That Shook Democrats,” New York Times (June 11, 2023)

Even black Americans are conflicted about affirmative action.

Though the result was anticipated, Karsonya Wise Whitehead, 54, a college professor, said she was so devastated that she had to sit down to process “the type of history being made at that moment.”

Her husband, Johnnie Whitehead, 59, the principal of a Christian school, said he took no joy in the ruling but was ambivalent about affirmative action. He is hopeful that it is no longer needed, but fears it is.

The eldest son, Kofi, 22, texted his brother Amir to share the news, and thought of the chilling effect it might have on the next generation of Black students. Amir, 20, felt that ending affirmative action was not wrong because admissions should be based upon merits only.

“One Black Family, One Affirmative Action Ruling, and Lots of Thoughts,” New York Times (July 2, 2023)

My take is that SCOTUS made the right call. In 2003, Justice Sandra Day O'Connor wrote, “We expect that 25 years from now, the use of racial preferences will no longer be necessary to further the interest approved today.” Using preferences to fight racism was a temporary solution whose time would end. Last week the Court said that the end had come, a decision with which most Americans agree.

California banned affirmative action at state schools in 1996, but those schools enacted admissions policies that roughly replicated their pre-ban student demographics. Black enrollment at the University of California now is 5%, and black people make up 5% of California’s population. The Ivies can and almost certainly will do similar jiggling of the system to achieve the same goal (and more quickly because they have models like UCLA’s example to work from).

Student Loans

The student loan forgiveness ruling, Biden v. Nebraska, seems completely reasonable. From the start, the arguments favoring Biden’s magic elimination of student loan debt were weak.

How can the president erase hundreds of billions of dollars of debt with the stroke of a pen? Doesn’t Congress hold the pursestrings? The rationale was that The Heroes Act gave the Secretary of Education the power to “waive or modify” programs in response to emergencies, and the COVID crisis was just such an emergency, but that seems a giant stretch. We had a vaccine for COVID, lockdowns were ending, and the economy was back on track. In what way was COVID an emergency requiring immediate action on student debt?

A lot revolves around the word “waive.”

What is the limiting principle here? Could the Secretary literally abolish all payment of all student loans? Could he abolish all future payments too and essentially turn student loans into unrestricted grants? Could he refund all previous loan payments? For that matter, what stops him from abolishing the loans and then giving everyone $50,000 free and clear to make up for the hardship they've been caused in the past?

I know: this is ridiculous. And yet, the law contains no explicit limit on the Secretary's power, which means there must be an implicit one. But what?

“Why can the Supreme Court overturn the student loan forgiveness program?” Kevin Drum (July 5, 2023)

Given that lack of clarity (which was Congress’s fault), the Court ruled that Secretary of Education Cardona and President Biden had gone too far.

The case was judged on the legal merits, but Biden’s plan also struck me as unfair. Most kids don’t go to college, and those who do often go to cheap community colleges and accumulate little debt. Debt forgiveness helps kids who have gone to expensive schools whose degrees will give them a leg up on everyone else. It is a massive transfer of wealth to the middle and upper classes. Even before loan forgiveness, those kids were going to end up far wealthier than their non-college contemporaries.

Of course, not everyone gets a degree in medicine or law. If you’ve spent $146,480 to get an MFA at Columbia (not including living expenses), you’re going to be hard-pressed to pay that off working as an adjunct lecturer at Hunter College, but why do you deserve the money more than a farm worker in Iowa or a janitor in Oakland?

The loan forgiveness plan was also pretty obviously politically motivated. As the Wall Street Journal put it:

The Supreme Court threw out the Biden administration’s plan to forgive student loans held by 40 million Americans, ending a $430 billion program the White House considers a crucial way to cement the president’s support among younger Americans.

I’d modestly benefit from Biden’s plan—my son has loans that were supposed to have been forgiven, and I still help him financially—but I think it’s wrong.1 I’m also leery of the growing power of the imperial presidency. Why would I want a Democratic president to expand his authority in a way that a Republican president will later abuse?

Free Homophobic Speech

303 Creative v. Elenis2 is the case that troubles me the most.

In the other two cases, I sympathize with all sides. There are a limited number of seats at elite institutions, and it’s understandable that Asian kids would resent that their numbers were being trimmed (and their character insulted) to advance social justice interests, but wanting to make up for past racism is a laudable cause. Likewise, I can understand both the pain of those overburdened with student debt and the anger of those who don’t want to pay someone else’s bills. With 303 Creative, however, the only motivation I see is bigotry.

The problem is, within certain parameters, Americans have the right to be bigots. The law is clear that businesses can’t refuse to serve clients because of their sexual orientation, but that doesn’t mean they have to say anything a client wishes. Lorie Smith at 303 Creative didn't want to be forced to design a website for something she was morally opposed to, a gay wedding.

Note that there was no actual wedding being planned. This was a purely hypothetical case based on a hypothetical query for a wedding website, a query that may never have happened. This doesn’t invalidate the case. Both parties to the suit stipulated the facts of the case, which was understood to be speculative anyway because Smith hadn’t started designing any wedding sites. Colorado likely assumed that some case would be brought, so why not accept and fight this one?

The would-be customer’s request was not the basis for Smith’s original lawsuit, nor was it cited by the high court as the reason for ruling in her favor. Legal standing, or the right to bring a lawsuit, generally requires the person bringing the case to show that they have suffered some sort of harm. But pre-enforcement challenges — like the one Smith brought — are allowed in certain cases if the person can show they face a credible threat of prosecution or sanctions unless they conform to the law.

“Legitimacy of ‘customer’ in Supreme Court gay rights case raises ethical, legal flags,” AP News.

Before the case came to trial, Smith and Colorado agreed to certain “stipulations” as facts. (Stipulations are facts both sides admit are true ahead of time to speed up the trial process.) Critically, they both agreed that Smith’s work was “expressive,” meaning it fell under the purvey of the First Amendment’s free speech protections.

This seems to be where the case was lost. Once the State (Colorado) agreed with the stipulation that Smith’s work was expressive, it became a First Amendment issue. Forced speech is not free speech.

On a gut level, it makes sense. If I were a website designer, I would not want to design a website for groups I disagree with, like anti-abortion activists, or a wedding site for a couple who bragged about their racial purity. (“We are unifying our two white souls!”) I would be angry if a court insisted that I express views that I found abhorrent.

This does not mean gay couples can be excluded from Christian stores. If your store sells banners that read “Hooray for our marriage!” it can’t exclude couples who are gay (or black or atheists) from buying one of those banners. If a business prints banners with personalized messages, however, it can say no to a message with which it doesn’t agree.

Journalist Josh Barro (who is gay) argues that SCOTUS’s decision was reasonable. He points out that it is very limited in scope.

It’s important to note that the decision is not just limited to “expressive” business activities (a category which the courts will have to define more clearly in future cases). It is also limited to cases in which the business owner is motivated to discriminate by the content of the expression. That is, while 303 Creative allows a web designer to refuse to make a website for a gay wedding, it does not allow a web designer to refuse to make a website for a gay client where the designer has no underlying objection to the web site content.

Barro also sees optimism given the context of Bostock v Clayton County (2020). In Bostock, Court ruled (in a 6-3 decision) that the Civil Rights Act of 1964 protects gay and transgender employees from employment discrimination.

Finally, to zoom out, I want to compare this decision to Bostock. Bostock did far more to expand the reach of non-discrimination law in employment than 303 Creative does to narrow the reach of non-discrimination law in public accommodations. Non-discrimination is also a more important policy objective in employment than it is in public accommodations. As such, the net effect of recent Supreme Court jurisprudence in this area — through decisions written, in both cases, by Justice Gorsuch — has been to expand protections and improve the policy environment. So I think that’s reason to feel pretty good about where things have been going.

“Thoughts On This Week's Supreme Court Decisions” Josh Barro (June 30, 2023)

I think free speech, even loathsome speech, needs protecting, and sometimes, protecting that speech may also protect the words or censoriousness of bigots.

Alone

That I disagree with apocalyptic takes on Facebook is not shocking. People get to have different views. Maybe I’m wrong about mine. What bums me out is the seeming unanimity of my tribe, with no hint that there may be other ways to view these cases. Agree with us or you’re supporting bigots.

This one-sidedness is common everywhere, perhaps even more so on the right, with Trump partisans ignoring any evidence against their hero and denouncing the Court when it refused to overturn the 2020 election.

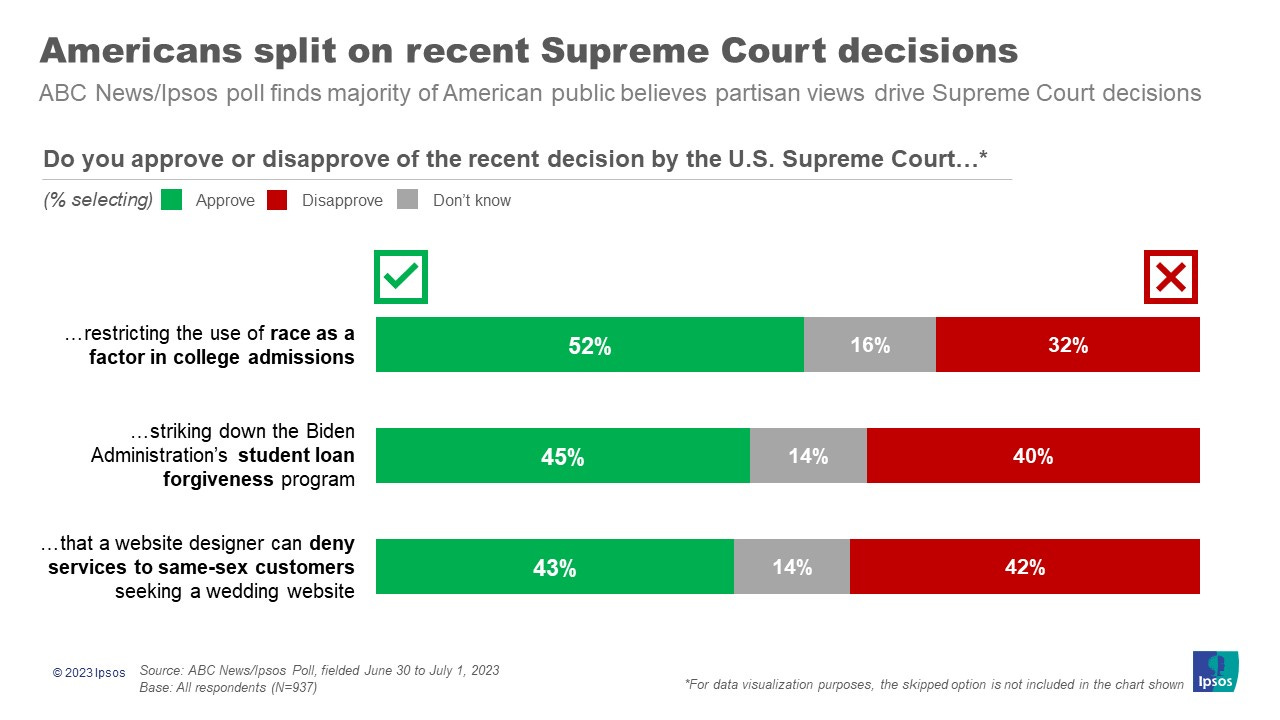

Of course, I’m not really alone. America is quite divided on all the Supreme Court’s rulings. A majority supported the affirmative action ruling, but the country is almost evenly split on loan forgiveness and denying a wedding website. Unanimity only exists if you’re listening to an echo chamber.

Kevin Drum (an old-fashioned liberal, formerly of Mother Jones) also thinks the Court’s rulings were reasonable:

The Supreme Court ended its term with a flurry of important decisions that covered a lot of important ground. How did it do? There are some clunkers on the list, but overall I think their performance was better than most liberals give credit for.

We live in binary times. For non-binary types, that can feel lonely, but only if you listen to the loudest voices on each side.

Full disclosure: He only owes 14k, so while the plan would help, it’s not a huge deal for me.

The full case name is 303 Creative v. Aubrey Elenis et al.—Elenis is the director of the Colorado Civil Rights Division.

As someone who is relatively moderate/centrist, but has maybe never voted for a Republican (I may have voted for Bloomberg once), I agree with you on all points. In particular, I agree with your take that, once they admitted the website in 303 was "expressive speech" the game was over - there is a decent argument that creative work for pay isn't expressive speech for Firag Amendment purposes, but they gave that up.

I was really disappointed in a lot of commentators, particularly Dahlia Lithwick, as they sought to portray these three ruling as a lawless SCOTUS rejecting precedent. There is probably room to disagree with SCOTUS on all three, but these decisions were not Dobbs or Janus, where the GOP appointees reversed establish precedent because they could. 303 was clearly SCOTUS defining the very edges of the boundary between Free Speech and anti-discrimination law, everyone knew that the legal justification for student loan forgiveness was tenuous (Biden said as much) and as you point out the Grutter precedent was that AA was only good for another 25 years. If you are telling me that these three decisions are radical departures from precedent, I now need to doubt you any time you make thet claim in the future.

The one caveat I'd make is that I'm a little concerned thst 303 might turn out to be a beach head from which a lot of anti-discrimination law gets overturned. 403 had really good (stipulated) facts, so I see why SCOTUS decided it the way it did. The question is how will that decision be applied the next time the 5th Circuit gets a case with less favorable facts. Are they going to hold that a car wash is expressive speech, and so the local car wash can reject all Subaru owners? But this is only a speculative fear at this point.

Good post.

I've said this in other places, but it bares repeating: as a gay man I would not want someone who thinks my marriage is bunk (and I'm going to hell) to make my wedding website. I don't want that person putting the icing on my wedding cake and I don't want them managing the wedding. Why (WHY?!) would ANY gay couple insist on the right of having a bigot plan their wedding? This seems absolutely asinine to me.