Pride

It’s Pride Month, which means 30 days of everyone frolicking in a friendly froth of fabulousness and fun.

If only.

In reality land, it will be 30 days of people getting apoplectic over the rainbows in their Starbucks frappuccino and the non-binary character in their kid’s school play. In December, we get the War on Christmas; June brings fears of the LGBTQIA2S+ mafia takeover.

Pride flags can seem omnipresent in certain spaces, but they’re hardly everywhere. I doubt you’ll see very many gay rainbows in Birmingham, Alabama. And we shouldn’t forget there is a reason for all those flags.

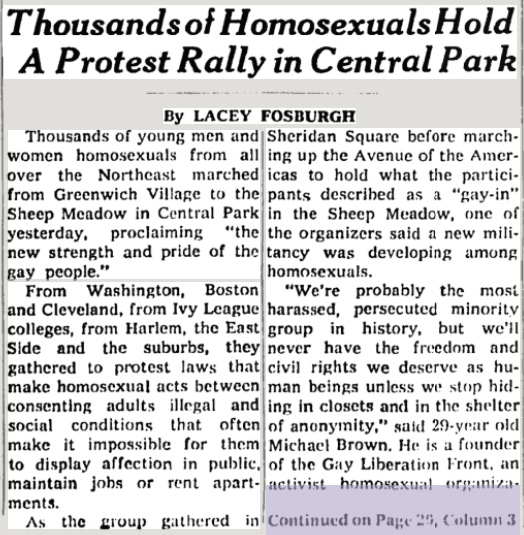

Back in ancient times, like the 1960s, gay1 people in America faced brutal discrimination. In New York City, police regularly raided the city’s gay bars, beating up and arresting patrons and publicizing their names. On the evening of June 28, 1969, the frustrated patrons of the Stonewall Inn in Greenwich Village fought back against the cops. The following year, inspired by that revolutionary moment, gay men and women organized New York’s first Gay Pride Parade (other parades took place that same year in Los Angeles and Chicago).

This didn’t lead to overnight acceptance of gay people. The parades grew bigger, the flags more numerous (today’s rainbow flag was designed in 1978), and the preferred labels changed (LGBTQ replaced gay), but gay people still suffered discrimination and violence. Until a mere twenty years ago (Lawrence v. Texas (2003), same-sex sex was illegal in 14 states. Even after the 2015 milestone of Obergefell v. Hodges, the Supreme Court decision that legalized same-sex marriage, gay folks are still getting beaten up just for being themselves. For LGBTQ people, “the past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

In 2021, the FBI reported that 19.1% of all hate crimes targeted people because of their sexual orientation (15.9%) or gender identity (3.2%). Those FBI numbers are incomplete and don’t include the abuse LGBTQ people receive from families who reject who they are. Homophobia and related bigotries have declined but not disappeared.

And then there was AIDS. The AIDS crisis wasn’t central to my world—I didn’t have close gay friends then—but I couldn’t not see the pain it was causing the gay community. The government ignored it. The AIDS epidemic began in 1981, but President Ronald Reagan didn’t mention it until 1985. Even the liberal New York Times avoided the topic for years. “You knew to avoid it. It was a self-reinforcing edict: Don’t write about queers.” I remember ugly AIDS-themed jokes told by comedians and people I knew. Even good liberals turned hostile. I was shocked by a professor who wondered to me whether her apartment building was safe because one of the residents was a gay man with AIDS. Two acquaintances I knew from nerdy gaming sessions died from the disease. Gay men felt that the straight world not only didn’t care that they were dying, but some bigots were actively cheering the plague.

Years later, I heard stories from my friend Steven about the pain and isolation he felt growing up gay in Indiana. While I was worried that some girl might hurt my feelings, he was ashamed of his “immoral” desires and worried that he might get beaten up. Coming to New York with its more open attitude was a kind of salvation, although his struggles didn’t disappear overnight. Today he’s a happily married man (and his husband cooks a killer chocolate cake), but he still worries about violence. Homophobic jokes overheard, politicians condemning the “gay agenda,” all these make his threat meter rise. When he sees the Pride flag, he feels a bit safer.

I also have family stories. Somewhere in the 2000s, I began to hear about my cousin “Sally’s” friend “Debby.”2 “Friend”? I wasn’t close to Sally, but I kinda suspected that Debby was more than a friend. In the early 2000s, however, “lesbian” was still not a word used in many families, certainly not in mine.

I later became closer to them and learned how they became “friends.” They had separately been pressured to go to a gay deprogramming camp, one of those places that are supposed to “pray the gay away.” My cousin went because she would have been fired from her job as a teacher at a conservative school if she didn’t go. Her future wife, Debby, went out of a sense of guilt over her “wrong” feelings. They met that first day and quickly realized that the de-gaying camp was going to have the opposite effect! That’s a sweet ending, but it can’t hide that they’d been sent to a place that was supposed to guilt and terrorize them into being something that they weren’t. (Watch the powerful Netflix documentary, Pray Away to hear more about the insanity of these programs.)

When they finally legally could, Sally and Debby married and had two lovely kids. (Not to feed lesbian stereotypes too much, but today they’re both sports-crazy soccer and karate moms!)

Then seven years ago, the Pulse nightclub shooting happened. A Muslim man opened fire at a gay club, killing 49 people. We now know his motivation was anger at America’s foreign policy, but at the time, it was naturally assumed he had deliberately targeted the LGBTQ community. People were afraid.

Among the fearful were my cousins’ kids. The news was too big to be hidden, and the kids were afraid that someone would want to hurt their moms. To reassure them that everything was ok, their straight neighbors put up rainbow Pride flags outside their houses so the kids would know that the community stood behind their moms and them.

Pride does many things, but one of them is to reassure LGBTQ folks that their communities have their backs and they aren’t going to get beaten up or killed just for being themselves.

So why would anyone have a problem with Pride flags?

Two answers stand out.

First, some LGBTQ people do things in the name of Pride that alienates those who might otherwise be sympathetic. When activists target JK Rowling with hateful slurs and threats or ask that Kathleen Stock’s invitation to speak at Oxford be rescinded, that upsets people. Their anger at activists spills over into hostility towards the rainbow flag.

There is also some hostility from within the gay community towards what they see as an extreme trans agenda. The LGB Alliance in Britain uses slogans like “stop transing the gay away.” Some gay folks even use the ugly slur “groomer” against trans activists.3

Of course, a ton of rainbow flag hostility originates from where it’s always been in style: Christian conservatives. Dale Partridge, a minister (and author of The Manliness of Christ: How the Masculinity of Jesus Eradicates Effeminate Christianity), finishes the below tweet by saying, “Any person who believes they can boast in their sin will soon face the God who destroys sinners.”

Or take Pastor Tom Ascol, who quotes from a passage in Leviticus, to suggest gay men should be put to death. (And for once, I agree with Ted Cruz, which gives me a very odd feeling.)

These two pastors are not exactly outliers. A significant minority of Americans still view all LGBTQ people as moral threats to America.

Gallup Surveys

Gay marriage should not be valid - 28%

Gay sex is morally wrong - 25%

Changing one’s gender is morally wrong - 51%

Gay sex between consenting adults should be illegal - 18%

(Although, oddly, only 5% think LGBTQ Americans should suffer employment discrimination. They may be bigots but most Americans think everyone has the same right to work.)

All this says to me that bigotry against LGBTQ people in America has lessened but not disappeared.

For Pride, I’ll be wearing my old-school “Gay Rights Are Human Rights” button. I want to visibly show my support for my cousins and my friend Steven. I understand some of the upset at parts of the LGBTQ world, but that’s not a reason to condemn all of Pride.

Take the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, a bawdy troop of drag queens who mock the Catholic Church. I have found their performances funny (if sometimes also boring and unimaginative), but I can see why some might think they don’t belong at a Dodgers game. So instead of condemning Pride, write letters to the Dodgers’ management, or protest outside the stadium.

The same goes for trans activists attacking JK Rowling and others. Some of their words are wrong and hateful, but they don’t represent all LGBTQ people. They don’t even represent all trans people! Oppose their bad behavior but don’t shun Pride.

I don’t agree with everything done under the American flag, far from it, but I still feel patriotic in my quirky liberal way. I feel the same way about the Pride flag. I’m wearing it to support my LGBTQ friends, family, and fellow Americans, many of them serving under this flag in our armed forces. I’ll push back against ideas I think are bad, but I’m not tossing out either flag.

I’m going to go back and forth with what to call people who aren’t heterosexual. I’m starting with “gay” because that used to be the more common catch-all label, and switching in “LGBTQ” later as that becomes the more accepted term. “Gay” as a term for someone homosexual dates back to at least 1950. “Queer” has become quite common today but it includes such a wide range of people that I’m not sure if it means the same thing at all.

Some names were changed to protect those who didn’t ask to be in one of my essays!

“Groomer” originally referred to a pedophile (usually a heterosexual man) bringing a young child into their orbit so they could be sexually abused. Because gay men have historically been accused of seducing young boys, the accusation of being a “groomer” has a nasty sting. It is disturbing to see the word “groomer,” with its pedophile history, being used these days to describe a far wider range of people.

Wonderful article

One thing I try to make clear to people: the US is actually a quite welcoming place to gay people (in particular). I live in Cleveland, Ohio. I came out less than a decade ago, but I have never (once) in my life been called a slur. Only three people in my life have reacted negatively to my sexuality; the one I will mention was an Evangelical Christian who, I might add, never had the courage to say what he felt to my face (we work in the same industry and he will not speak to me).

That is NOT to say that homophobia/transphobia doesn't exist. Of course it does: but there are few places in the world 'better' to be gay than here, and I am grateful to live in the US happily married trying to have kids. I don't really go to Pride events much, but I fully support Pride. I find the disgust from conservatives baffling.

Good article Boomer! You should be.....proud!