Police violence

On January 7, 2023, a young black man named Tyre Nichols1 was brutally beaten by five police officers after a traffic stop. As he was being pummeled he called out “I’m just trying to go home” and “Mom, Mom, Mom.” He lived with his mother and stepfather about 100 yards from where he was assaulted. Three days later he died from his injuries. The ugly scenes of the beating were caught on video from bodycams and surveillance footage. The officers, oblivious to being filmed, seemed to think their badges would shield them from consequences. Instead, they have been dismissed and are facing murder charges. Now America must again wrestle with the issue of police violence.

Only in America?

To understand what happened we need some context. This doesn’t just happen in America. Almost every police force kills civilians, sometimes unarmed civilians.

—The Guardian “Jamaica police commit 'hundreds of unlawful killings' yearly, Amnesty says” (Novemeber 2016)

— Los Angeles Times, “‘The police come here to hunt’: Brazilian cops kill at 9 times the rate of U.S. law enforcement” (October 2022)

The United States is 32nd on Wikipedia’s list of killings per capita by law enforcement, with 34 people killed per 10 million population. This puts America on par with Mexico (30 per 10 million) and Colombia (34 per 10 million). This is not great. The United States is far worse than other rich countries. Canadian law enforcement kills people at less than one-third of America’s rate.

Is racism the reason America is so high on this list?

The five officers who beat Tyre Nichols were black, their police chief was also black, and 58 percent of the Memphis Police Department is black (in a city that is 64 percent black). Can racism be blamed when black cops beat a black man to death?

Thomas Zimmer, a historian at Georgetown University, blames “white supremacy” and “structural racism.”

Only Black men know what it’s like to live in a system in which every interaction with the police could easily turn into a life-threatening situation;

Except “only Black men” is not true.

In very white (93 percent) West Virginia, 77 people were shot and killed by the police between 2015 and 2022, according to the Washington Post Police Shooting Database.2 The race of 61 is listed, and 52 of those (85%) were white. Are the police of West Virginia killing white people because of white supremacy and structural racism?

And what about countries where the police are more violent than in America? Is police violence in Jamaica, the Dominican Republic, or Honduras caused by white supremacy? Even tiny Netherlands has police homicides.

Dutch police fired their guns in just 16 incidents last year [2019], resulting in four deaths and 12 injuries

— DutchNews.nl

In the United States, more white people are killed by the police every year than black or Hispanic people but these killings receive less media attention.

“Where Police Killings Often Meet With Silence: Rural America”

As fatal police shootings have become a flashpoint in U.S. cities, they have also occurred at high rates in rural areas — largely without national attention.

— New York Times (August 13, 2021)

According to Mapping Police Violence, 1144 people were killed by the police in 2020. Of those, 416 were white, 257 were black, and 202 were Hispanic (in some cases the race of the victim was unknown). The Washington Post database—which has lower numbers because they only count those killed by guns—lists 1019 victims, with 459 white, 242 black, and 172 Hispanic. In the great majority of cases, the victims were armed.3 (Numbers vary between these two lists because there is no national registry of police victims. Every organization has to come up with its own method of totaling the slain.)

It is true that compared to their share of America’s population (13.6 percent) more black people are killed by the police but proportionately more crime is committed by black people and so police will inevitably have more fraught encounters with black people. Obviously, this does not mean that black people are more prone to commit crimes—Tyre Nichols was guilty of nothing but wanting to go home—but a tiny subset of young black men does commit, and are victims of, a disproportionate number of murders. These young men get a disproportionate share of police attention.

Of course, mentioning crime in this context can lead to accusations of racism. Back in 2020, progressive journalist Lee Fang was viciously attacked because he posted a video interview with a black man who said he was worried about black people being murdered by other black people. After a massive Twitter pile-on and criticism from colleagues, Fang was forced to apologize.

The backlash faced by Fang illustrates that while it’s acceptable in some progressive circles to talk about disparities in police violence it’s taboo to talk about racial disparities in crime. The result of this skewed emphasis is that some on the left (I’ve spoken to them) literally believe that more black men are killed by the police than are murdered.

Young Black men and teens made up more than a third of firearm homicide victims in the USA in 2019, one of several disparities revealed in a review of gun mortality data released Tuesday by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The analysis, titled "A Public Health Crisis in the Making," found that although Black men and boys ages 15 to 34 make up just 2% of the nation's population, they were among 37% of gun homicides that year.

— “Young Black men and teens are killed by guns 20 times more than their white counterparts, CDC data shows",” USA Today, Feb 23, 2021.

An August 2019 study in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences took crime into account and concluded “We did not find evidence for anti-Black or anti-Hispanic disparity in police use of force across all shootings.” Roland Fryer, an economist at Harvard, also investigated the data and concluded that while “there are large racial differences in police use of nonlethal force” (meaning black civilians were more likely to face physical violence) “we didn’t find racial differences in officer-involved shootings.” (“What the Data Say About Police,” Wall Street Journal, June 22, 2020).

Given the history of racism in America, these studies may not convince some Americans.

The concept of systemic racism posits that there are racist structures hard-wired into American institutions that lead to racist outcomes. That idea is reasonable—America has a long and ugly history of racism—but we can’t simply wave a wand and say “systemic racism” or “white supremacy” without explaining how those played out in a particular case. How exactly did the allegedly systemically racist training of the Memphis police lead to racist outcomes?

Perhaps it’s because it’s not the racist police but an economic system that makes poor people of all races targets?

In 2021, Kenan Malik said that “US policing is far less about fighting crime than controlling the poor.” Malik argued that keeping the lower classes in order has always been a primary goal of policing.

While racial biases are clear, studies suggest poverty and class best correlate with police killings and mass incarceration. African Americans, more likely to be working class and poor, are also more likely to be imprisoned and killed. It is, however, an issue confronting all “lower-class” people.

Social and medical issues, from mental illness to homelessness, are also seen as issues for “warrior cops”, often with tragic consequences. If you’re poor or black, it is likely that much of your life is lived in the shadow of the police.

Thirty-eight million Americans live in poverty. Being poor doesn’t make anyone a criminal—most poor people aren’t breaking the law—but it does leave them far more vulnerable to societal ills. And when rich people commit crimes, they’re mostly the kind that good lawyers can have erased. The police never shoot insider traders.

Slave Patrols

For those who insist that it’s not an unjust society but that the police themselves are systemically racist, one common explanation offered is “slave patrols.”

In 2020, historian Jill Lapore wrote:

The police,” as a civil force charged with deterring crime, came to the United States from England and is generally associated with monarchy—“keeping the king’s peace”—which makes it surprising that, in the antimonarchical United States, it got so big, so fast. The reason is, mainly, slavery.

Lapore’s article, written in the shadow of George Floyd’s murder, tries to force a connection with Southern slavery while providing no clear evidence.

It is often said that Britain created the police, and the United States copied it. One could argue that the reverse is true.

That “one could argue” is doing a lot of work here.

The widely repeated slave patrols idea is one of the sources of the “defund the police” argument. If the police began with slave patrols they are irredeemably tainted by the original sin of racism. For extremists, therefore, the only possible answer is to “abolish the police.”

The belief that police originated with slave patrols is nonsense.

Every country on the planet has police. India has 2 million, France almost three hundred thousand. Even tiny Liechtenstein has 91.

Crime is not a new thing. The Code of Hammurabi said, “If a man breaks into a house, they shall kill him and hang him in front of that very breach.” “If a builder builds a house for a man and does not make its construction sound, and the house which he has built collapses and causes the death of the owner of the house, the builder shall be put to death.” (Harsh.)

Emperor Augustus created the urban cohorts to keep peace in the streets—particularly important as Rome was often troubled by criminal gangs—while night watchmen called vigiles handled petty crime. In Tokugawa Japan, there were systems of magistrates and criminal investigators, all samurai. At the Kozukappara execution grounds near Edo, more than 100,000 criminals were killed during the Tokugawa era. Early modern England had a haphazard system of country constables, town watchmen, and justices of the peace. Hanging was a common punishment for everything from murder to petty larceny. In 1724, famed thief Jack Sheppard (“Honest Jack”) was hanged at Tyburn before a crowd of 200,000. In 1749, modernizing Judge Henry Fielding organized a system of roving constables known as the Bow Street Runners.

The British professionalized their policing in 1829 with the creation of the Metropolitan Police Service, run by Sir Robert Peel. (At first, they were nicknamed “Peelers,” not today’s more common “Bobby.”) This may be the first uniformed police force (the French claim otherwise) and it became a model for modern police forces around the world.

The American colonies, true to their British roots, also had a system of watchmen and constables but when the British demonstrated a better way, the Americans were quick to copy it. British-style police forces were created in Boston (1838) and New York (1844). Other cities followed suit. None of these early American police forces were based on slave patrols.

The defund and abolish the police slogans are wrapped up in a fantasy that it is only the police—systemically racist—who do evil things and if we could only manage to get rid of them—to be replaced with social workers and jobs programs—we would all live in utopian peace and harmony. (Although I do think we should have more social workers and jobs programs.)

If policing is rooted in white supremacy, why did white people hang white Honest Jack Sheppard? Why do Japan, China, and Nigeria all have substantial police forces? Are they also systemically racist? It’s remarkably arrogant to think that everything bad, including policing, began with the United States and its institutions. We’re not that special.

Why are so many civilians killed?

In August 2007, Melissa Borton (who is white) was pulled over while driving home with her 2-month-old child. Officer Derek Chauvin—without uttering a word—violently yanked her out of her minivan, leaving behind her screaming child, and put her in his patrol car because her van “matched a description.” She was soon released and filed a complaint but nothing came of it. Chauvin continued to work as a cop until he killed George Floyd 13 years later.

On January 18, 2016, Daniel Shaver was showing off his air rifle to friends in a La Quinta Inn suite and someone called the police because at one point he had pointed it out the window. The police arrived and took his female friend into custody and ordered Shaver to lie prone on the ground. The grim scene is caught on video as police yell contradictory commands to a sobbing Shaver, ordering him to successively cross his legs, kneel, and crawl. As Shaver, who is white, is begging not to be shot, Officer Philip Brailsford shoots and kills him. Brailsford was charged but acquitted of murder. He was allowed to take a medical retirement with a partial pension.

In August 2019, a young autistic black man named Elijah McClain (who worked as a massage therapist and played the violin to soothe stray cats) was stopped by police because someone thought he “looked sketchy.” He was restrained by cops using an illegal choke hold, injected with a sedative by paramedics, and went into cardiac arrest. While restrained he vomited several times, apologizing “I’m sorry, I wasn’t trying to do that, I can’t breathe correctly.” Three days later, brain dead, he was removed from life support. The three police and two paramedics involved have been charged with manslaughter and will be tried later in 2023.

The stories are endless and the grim problem of civilian deaths remains. Why are American cops involved in so many violent confrontations?

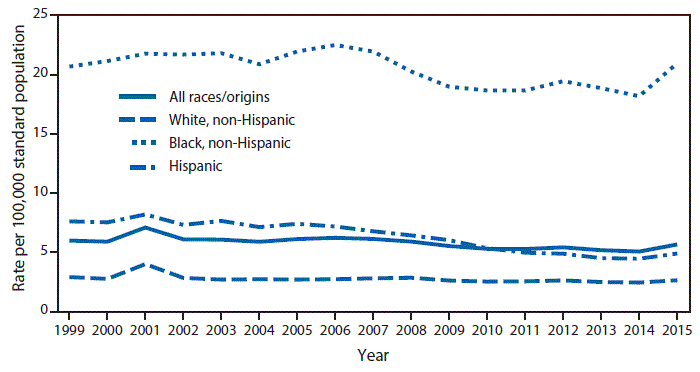

One obvious answer is that the United States is a very violent society. We do a lot of murder. The CDC reports that 26,031 people died from homicide in 2021. In terms of risk, murder is far more of a threat than police killings, especially for black men. Based on FBI figures, more than half of murder victims were black. Black men are roughly nine times more likely to be murdered than white men. The disparity is stark. There really are two Americas.

America’s overall homicide rate in 2021 was 7.8 per 100,000 population. Most European countries have rates between 0.5 (Switzerland) and 1.6 (Finland). The United States has six times the murder rate of France (1.3 per 100,000) and twenty-five times that of Japan (0.3 per 100,000). Given these numbers, an American cop is much more likely to encounter violence than a French gardien de la paix or a Japanese omawari-san.

And what about all those guns?

There are about 120 guns for every 100 Americans. Forty percent of American households have a gun. Other countries have highish rates of gun ownership (Finland 32 per 100, France 20 per 100) but more tightly regulate and track those guns. An American cop is much more likely to confront an armed civilian on the street than any of his European counterparts and so every encounter cannot help but feel more dangerous and thus more likely to lead to deadly mistakes. Some police violence is probably a downstream effect of so many guns.

The fear that an American cop faces is not unfounded. American police are at higher risk than their European counterparts.

Unlike in the United States, where there are more than 100 such fatalities in a typical year, fewer than a dozen French police officers are killed annually, and sometimes the number is as low as a half-dozen.

Given the more violent nature of American society and the much higher rates of gun ownership, police violence becomes somewhat more understandable, which is not to say forgivable. Remember, Elijah McClain wasn’t carrying a gun when the police restrained and choked him. Daniel Shaver was on the ground begging for his life. Why are the police violent in so many situations where violence is clearly unnecessary?

America has a police departmentS problem

Americans have no national police force. Instead, there are about 18,000 law enforcement agencies in the United States, each with its own rules and systems of training. It’s distorting to look at America’s police as a monolithic entity.

From 2015 to 2022, New York had more total police killings than any city listed below except Chicago, but taking into account killings compared to population, Baltimore and Detroit had police departments that were relatively far more deadly. The average citizen of Baltimore was ten times more likely to be killed by a cop than the average person in New York.

Of course, this doesn’t factor in crime. Baltimore and Memphis have more police-caused fatalities than New York but they also have higher homicide rates. My point was not to show that New York was better than New Orleans but to illustrate that the seriousness of this problem varies significantly by department.

Why?

Besides crime rates, one possible answer is training. American police are probably undertrained, getting far less training than their European counterparts.

Training varies widely between police departments in the United States, both in hours and quality. Two of the Minneapolis cops who watched while George Floyd was being murdered were rookies fresh out of the academy who had only trained for 16 weeks. New York requires police cadets to train for 26 weeks, still incredibly short by European standards. The Memphis Police Academy, responsible for the officers who confronted Tyre Nichols, trains its officers for 21 weeks.

American police departments are also understaffed. The United States has an average of 242 law enforcement officers per 100,000 population. Compare that to Germany with 349 per 100k, France with 422 per 100k, and Italy with 456 per 100k. Remember again that the United States is a more violent country with a much higher homicide rate. Given its high crime rate, the United States has far too few police officers.

Exacerbating undertraining and understaffing, Americans are prone to creating police who act too much like soldiers. Journalist and author Radley Balko covered this tendency in his 2013 book, The Rise of the Warrior Cop: The Militarization of America’s Police Forces. The officers who beat Tyre Nichols were part of a special unit with the macho code name “SCORPION.” (Street Crimes Operation to Restore Peace in Our Neighbourhoods.4)

For 14 months, officers from the high-profile Scorpion unit of the Memphis Police Department patrolled city streets with an air of menace, zooming up on targets, jumping out of their Dodge Chargers at a dead run, shouting at people to get out of their vehicles, lie down on the ground.

They did it to Damecio Wilbourn, 28, and his brother as they pulled up to an apartment building last February. They surrounded Davitus Collier, 32, as he went to buy beer for his father in May. And last month, they beat Monterrious Harris, 22, outside an apartment complex, where he said he was waiting to spend time with his cousin.

— “Muscle Cars, Balaclavas and Fists: How the Scorpions Rolled Through Memphis,” New York Times, Feb 4, 2023

American police stations can seem like the fortresses of an occupying army. Compare this to Japan’s Kōban, small police stations serving local neighborhoods. The police attached to Kōban serve as local community liaisons, cheerfully offering directions and helping to find lost children. They are called omawari-san meaning roughly “those who walk around.” These aren’t warrior cops. The Japanese system wouldn’t translate perfectly to America but increased community policing might reduce violent encounters.

Improving policing is possible. New York City cops used to be far more prone to using their guns. In 1971, the NYPD discharged their firearms 810 times and killed 93 people. In 2021, they fired 52 times and killed 6 people. It’s true that the murder rate was three times higher in 1971 (1466 homicides vs 488 in 2021) but New York cops killed fifteen times as many people. New York City police today are less violent than they were fifty years ago.

Department accountability is a necessary part of reform. Most officers aren’t brutal—perhaps 5 to 10% are responsible for most misconduct complaints—but the misconduct of violent cops has often been hidden away behind a blue wall of silence. It’s possible charges would not have been filed in the Tyre Nichols case if Memphis had not in 2022 elected a progressive District Attorney, replacing a hardline Republican incumbent.

“If the previous district attorney were still in office, I believe Memphis would be on fire right now because I don’t think she would have charged anybody,” says Earle Fisher, a Baptist pastor and activist for police reform.

It’s also important to remember most people, including most black people, have no wish to defund or abolish the police, even with all their flaws.

Nekima Levy Armstrong, a black civil rights lawyer, is no fan of the police (“Minneapolis police have persistently abused Black residents”), but her Nov 2021 New York Times Opinion piece sharply condemned the idea of defunding the police. Her essay came out just days after Minneapolis voters had rejected a plan to replace the Minneapolis Police Department with a Department of Public Safety.

While many white progressives embraced the ballot measure as a sign of progress, many Black residents like me raised concerns that the plan lacked specificity and could reduce public safety in the Black community without increasing police accountability. The city’s largest Black neighborhoods voted it down, while support was greater in areas where more white liberals lived.

The proposal would have almost certainly created a cascade of unintended consequences that would have harmed Black residents by reducing the number of police officers and the quality of oversight without creating an effective alternative.

Black lives need to be valued not just when unjustly taken by the police, but when we are alive and demanding our right to be heard, to breathe, to live in safe neighborhoods and to enjoy the full benefits of our status as American citizens.

Survey after survey shows that voters don’t want the police defunded. This September 2021 Pew poll shows that Americans of both parties lean towards more police spending (or keeping things the same) and black Democrats want even more police spending than white Democrats.

This does not mean that black Americans—or any Americans—are satisfied with the police. They are frustrated by the endless stories of abuse at the hands of cops. As future New York mayor, Eric Adams said back in 2021:

“We make a mistake when we hear people say they don’t want police to be abusive,” Adams told me. “Some of us interpret that as We don’t want police. That is just not true. I challenge you: Go through these communities with high crime and you start telling them you are going to pull the police away. You are going to need a cop.”

So what to do?

Blaming everything on racism is a very bad idea. It distracts from the real factors that lead to excessive police violence. Does this mean cops are never racist? Of course not. But most police violence isn’t a result of racism. If every cop in America underwent extensive diversity training the police would still be killing too many people.

Some police violence is inevitable. Until we can somehow make America less violent (a worthy goal) we will have higher rates of violent police encounters than other rich countries. Some of these encounters, inevitably, will result in wrongful deaths. This doesn’t mean, however, we can’t manage to have fewer killings by law enforcement.

Reducing the size of our departments is madness. We have too few officers, not too many. Eliminating police to solve America’s violence problem is like reducing the number of doctors in order to reduce medical errors. The defund the police activists focused on having fewer police rather than on making our police better. This was a distracting error in strategy and messaging.

Better and more extensive training seems called for. America compares poorly to its peer countries. There are specific procedures that should be reconsidered (no-knock raids, punitive traffic stops, dangerous physical restraint methods). It should be easier to get rid of bad officers (police unions seem to be a real roadblock here). Police need accountability.

Demilitarizing the police is a priority. We don’t need more SCORPIONS. The police force needs to support the communities it serves, not act as an occupying army. Sometimes force is necessary—American cops can’t go unarmed like British bobbies—but the emphasis should be on de-escalation.

Whatever we do to improve our police forces requires serious thought rather than shallow slogans. A rich country should do better with its police and for its citizens. We have lost too many men like Tyre Nichols

Nichols was an avid skateboarder and photographer. He had a job at FedEx but he was coming home a bit late, possibly because he had stopped (as he often did) to take pictures of the sunset. (“From Sacramento to Memphis, Tyre Nichols Cut His Own Path”).

By keeping track of this information, the Washington Post provides a valuable resource. It is a shame that the United States does not track this vital information. https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/investigations/police-shootings-database/

Using a different methodology, the Mapping Police Violence people also track police killings (not just shootings).

https://mappingpoliceviolence.org/

Of the 1019 victims listed in the Washington Post database for 2020, only 60 were unarmed.

Who thinks up these crazy names?

This is an interesting analysis. As with most of America's broken systems, there are multiple factors at play, racism being just one.

You mention the overwhelming numbers of guns, which certainly make Americsn policing more dangerous than is the case in other countries, but you don't mention the fact that many police officers do not favor gun control. In fact, in response to a ban on assault weapons in IL, numerous sheriff's stated their intention to disregard this law. A measure that would increase safety for both civilian and police is not supported by the police.

I may have missed it, but qualified immunity confers a sense to American officers of being above the law...and attempts to prosecute police are often confounded by this arbitrary protection.

Finally, while I agree with your points about staffing and training, police departments are extraordinarily well funded in the US. The problem is that substantial funds are used for over-militarization (which you note) and hundreds of millions (if not more) on settlements for a wide variety of police misconduct.

Mote training alone is not the answer (and you don't suggest that this is the case), but structural changes are essential for training to be effective. Police unions instill a culture of 'us vs them' that's prevalent in police departments.

There are no simple solutions. Stricter guns laws, elimination of qualified immunity, changes to police unions, greater involvement in the community, enhanced training would all have to be implemented cohesively to effect real change.

A thoughtful and even-handed essay on a subject that could easily fill a book.

I've been curious to see some discussion of the lack of marches and the relatively meager public reaction compared to the Floyd murder. The Nichols murder on video looked at least as awful and violent as that of Floyd. Maybe the arrests so soon after the murder? Maybe most just didn't perceive racism. (Plus it's unimaginable that another DA wouldn't file charges.)

I tend to dislike the 'woke' verbiage of systemic racism and white supremacy. I think there is some poor reasoning and/ or co-opting of language. One interlocutor on Twitter said he couldn't imagine Nichols' assault happening to a white person, though, which rings true to me. I'd love to see ways to enhance economic opportunities for all the poor and won't complain too loudly if I must pay more taxes to do that.