Painting and Smoking

Adriaen Brouwer (1605-1638)

Adriaen Brouwer

I’ve fallen in love with “The Smokers,” by Adriaen Brouwer (on display at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art). Painted around 1636, it feels as up-to-date as any Instagram selfie. Brouwer sits center-stage in his own painting, looking up with faux open-mouthed surprise as we stare back at him and his buddies chilling in the afternoon. (Those buddies include painters Jan de Heem on the far right and Jan Cossiers on the far left.)

The scene is funny, even juvenile (we see Cossiers on the left blowing smoke out one nostril), and it erases the almost 400 years that separate us from Brouwer. His message seems to be that this painting isn’t some artificially posed scene (although, of course, it is); rather, this is a dude living a regular life, filled with belches, belly laughs, and smoking with the guys.

Today we frown at smokers but smoking in the 1630s was the cool new fad brought to Europe by the Spanish.1 After they arrived at Cuba, Christopher Columbus’s scouts found men who used strange devices to inhale smoke into their lungs.

and having lighted one part of it, by the other they suck, absorb, or receive that smoke inside with the breath, by which they become benumbed and almost drunk, and so it is said they do not feel fatigue. These, muskets as we will call them, they call tabacos.

By the 1530s, there were tobacco merchants in Portugal. Jean Nicot (from whose name we get “nicotine”) brought tobacco from Portugal to France in 1560. It was believed to have medicinal uses, including protection from the plague. Not everyone loved the new weed. The puritanical English tried to stem the tide of smokers. King James I called tobacco

as lothsome to the eye, hatefull to the Nose, harmefull to the braine, dangerous to the Lungs, and in the blacke stinking fume thereof, neerest resembling the horrible Stigian smoke of the pit that is bottomelesse. [i.e., hell]

But continental Europe was less judgemental and Brouwer and his friends show no guilt at having a pleasant smoke.

Depicting day-to-day life was Brouwer’s specialty and it makes his work timeless. We can all identify with the man who’s just gulped a nasty swig of medicine in “The Bitter Draught” (ca 1637). Brouwer painted a lot of folks in bars because where else is a painter going to be hanging out?

In “Peasants Brawling Over Cards,” Brouwer gives us a card game gone awry. Who hasn’t wanted to brain a rival when they suddenly reveal a pair of aces? Perhaps that ace on the floor had fallen out of Mr. Green-Shirt’s sleeve?

Information on Brouwer is sparse until he reaches his twenties. Biographers believe Brouwer was born around 1605 in the small Flemish City of Oudenaarde (in today’s Belgium, A on the map) which was then controlled by the Spanish Habsburgs. Around 1613ish his family probably moved to Gouda (B) in the Republic of the United Netherlands. At some point he moved to the big city of Amsterdam. In March 1625 he is documented as staying at an inn run by Amsterdam painter Barent van Someren. The following year he’s listed as a witness in an Amsterdam art sale. Around 1630 he moved to Antwerp (C), back again in the Spanish Netherlands. Those two towns—Amsterdam and Antwerp—were the happening places for cool artists in the 1630s.

Brouwer became friends with both Anton van Dyck and Pieter Paul Rubens (the guy famous for painting full-figured women). His work was also admired by Rembrandt, although they may not have met.

The Netherlands

There is way too much history wrapped up in the small chunk of land where Brouwer lived out his short life.2

Back in the 1400s, the entire Netherlands (which is today divided into Belgium and the Netherlands) was mostly controlled by the Dukes of Burgundy, a powerful branch of the French royal family that sometimes bossed around their royal bosses. These territories were then acquired via marriage by the Habsburgs, a German family that went around marrying all the right people until by the early 1500s they controlled about one-fifth of Europe. The biggest Habsburg of them all was Charles V (1500-1558). He was Holy Roman Emperor, Archduke of Austria, King of Spain (whose territories included much of Italy as well as the newly colonized Americas), and Lord of the Netherlands. When he retired (1556), Charles divided his lands into two separate Habsburg family domains—Spanish and Austrian—because it was just too damn much land for one king to handle.

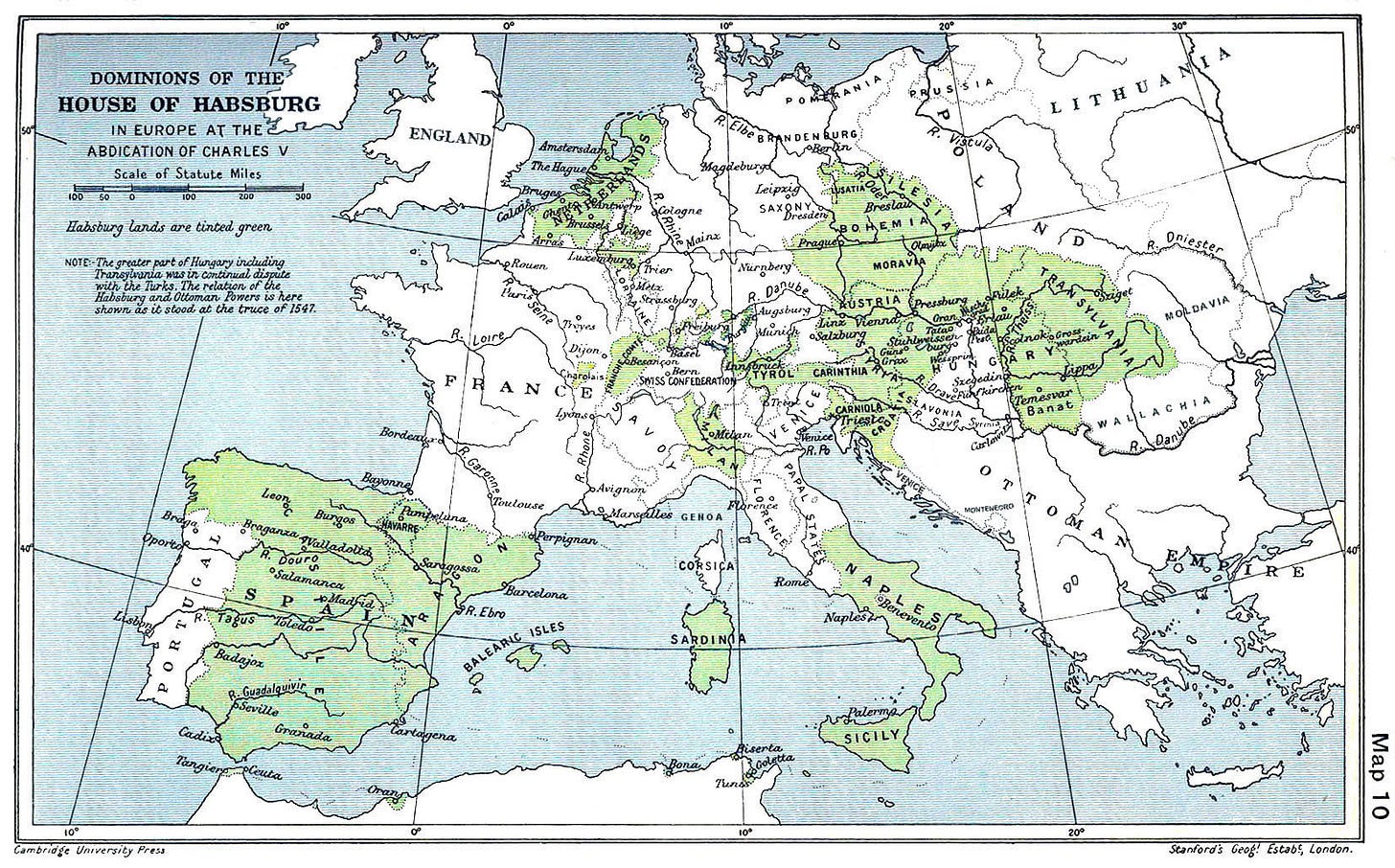

Below are Charles V’s territories (before the split) marked in green. The Netherlands is in the north, right across the channel from England. In the Habsburg split, the Netherlands went to the Spanish.

Independence for the North

Two things happened to shake up the Netherlands.

First, they started to get rich. Trade was increasing throughout Europe and much of it was centered around the canny merchants of Antwerp and Amsterdam. Local manufacturing led to Netherlands’ goods being shipped everywhere, which fed the Netherlands shipping industry. Soon Dutch ships were exploring and exploiting around the world. More wealth meant a thriving cultural scene. Rich merchants can afford to buy art from guys like Rembrandt and Brouwer.

Second, the Dutch got religion, a new one. Back in 1517, a German monk named Martin Luther challenged the Catholic Church’s authority to make all the rules for all Christians. He argued that every Christian had as much right to interpret the Bible as the Pope. This did not make the Pope happy. Luther quickly acquired followers and Europe was split between traditional Catholics and these new Protestants. The Netherlands had a sizable Protestant minority, but their Spanish rulers were Catholic and worked hard to stamp out a devilish heresy.

Repression made the Netherlanders grumpy and some began to dream of throwing off Habsburg rule. Open fighting broke out in the late 1560s beginning what historians call the Eighty Years War (1566-1648).

The war was brutal. In one campaign, the Duke of Alba, a Spanish general, captured Antwerp (1576), and his troops slaughtered seven thousand citizens in the streets, chanting “to blood, to the flesh, to fire, to sack!” The rebels, mostly Dutch Protestants, finally fought the mighty Spanish Empire to a draw, forcing an exhausted truce in 1609, four years after Brouwer’s birth. The northern Netherlands called itself the “Republic of the Seven United Netherlands,” (usually shortened to “The Dutch Republic” by historians), while the south, including Antwerp, remained under Spanish control.

The Thirty Years’ War

Then things got really bad for the rest of Europe.

The new trouble began in Bohemia (today’s Czech Republic), which was controlled by the Austrian Habsburgs. The Austrians were Catholic and like their Spanish cousins, they disliked Protestant troublemakers. In 1618, the Austrian emperor sent new administrators to run Bohemia, and an angry Protestant mob, fearing their religion might be attacked, poured into the governor’s palace in the capital city of Prague and threw the King’s flunkies out the window. Called the “Defenestration of Prague” this begins the cataclysmic Thirty Years’ War. The Bohemians called on other Protestant countries to help them, the Austrian Habsburgs called on their Spanish Habsburg cousins, and everyone settled down to murdering anyone who worshiped God in the wrong way.

The war was horrible but how it began remains pretty funny. I’m always tickled that there is a word—defenestration—that means “throw somebody out a window.” It’s like de-boning a fish, except you’re de-windowing a Catholic governor.3 Amazingly, the governors survived the 70-foot drop, probably because bad 17th-century sanitation had left large piles of garbage and excrement below the window to cushion their fall.

The Thirty Years’ War put all the Protestants on one side vs. the Habsburgs on the other and turned Germany into a bloody charnel house, killing between 4 and 8 million people long before we had invented machine guns or poison gas.

Actually, it was almost all the Catholics. The Catholic Kingdom of France joined with the Protestants because they wanted to take the Habsburgs down a few notches. (When you’re number two, you have to try harder.) The French double-cross was thought up by King Louix XIII's chief minister, Cardinal Richelieu, who even though a cardinal in the Catholic Church, was all about making France the #1 power in Europe. (Richelieu was later made the villain in Alexander Dumas’ The Three Musketeers.)

The brutality that had characterized the Spanish and Dutch conflict now spread to all of Europe. Catholics were eager to crush the Protestant heresy. Protestants were fighting the Satanic force of Catholicism. (Back in 1520, Martin Luther had already called the Pope “the Antichrist”). Anything was permitted when fighting such evil.

Jacques Callot, an artist from the Duchy of Lorraine (now in France), created a series of 18 images, “The Great Miseries of War” (1633), some of the first anti-war propaganda in European history. He portrayed a war of unrestrained cruelty. Formal battles were overshadowed by raiding homes, burning monasteries, murdering innocents, raping women, and horrific punishments including burning at the stake.

“The Hanging” part of “The Great Miseries of War” (1633) series by Jacques Callot

“The Pillage,” same series by Callot.

Brouwer again

When war broke out, Brouwer was in Spanish-controlled Antwerp, so technically he was on Team Catholic. As an artist, of course, he was more on Team Let’s Get Drunk And Then Paint What Happened.

I like this reminder that while great events are going on, people, artists included, still go about their lives. When Brouwer was painting “The Smokers,” the war in Europe had been raging for 18 years and had another 12 to go. It helped that most of the ugliest fighting took place in Germany, not the Netherlands. Still, you can’t completely ignore a war when you’re in the Spanish Netherlands and the Protestant Dutch Republic is to your north and the hostile Kingdom of France to the south.

Brouwer may even have been briefly caught up in the war’s clutches. In 1633, he was jailed and one theory is that he was suspected of being a Dutch spy. More likely, however, was that he was arrested for not paying his taxes (he was often in trouble for not paying debts).

In 1638, aged 32, Brouwer died. The cause is unknown but a likely guess is plague. The plague, known as “the Black Death,” may have killed half of Europe’s population (50 million people) between 1346 and 1353. After that, the plague faded but continued to reoccur in milder and more isolated incidents over the next few centuries. Brouwer’s death took place during one of these reoccurrences. The plague was more common in wartime, which jammed people into besieged cities and sent infected armies careening across the countryside.

Ten years after Brouwer’s death, the Thirty Years’ War ended. One-third of Germany’s population had died. What had started as a religious war had ended as a war for political dominance. If there was any winner it was France, which saw the power of the rival Habsburgs greatly reduced.

The Treaty of Westphalia (1648) recognized that fighting a war over beliefs was madness. Each ruler was allowed to determine the religion of his state without interference from other governments. Citizens within a country who differed could worship privately. It wasn’t really freedom of thought—persecution of religious minorities still occurred—but it was at least tolerance. ‘We don’t have to like that you’re a Satan-worshipping Catholic or Protestant, but we won’t go to war over it.’ This tolerant trend opened the door to the 18th century’s Age of Enlightenment, which in turn gave birth to constitutions that defended freedom of speech and worship.

If there’s a lesson for our own time it’s that trying to suppress ideas you don’t like rarely works out well. Brouwer offers some more mundane lessons: Spend time with your friends, live life to the fullest, and keep your sense of humor.

Portrait of Adriaen Brouwer by his friend Anthony van Dyck.

Years ago, before they’d gotten big, I saw Penn and Teller do a show in New York. Because they were magicians, the audience was filled with parents and kids. One trick involved a cigarette. Penn Jillette opened by saying “Kids, don’t smoke.” [pause] “Unless you want to look cool.” A hundred moms gasped. It was beautiful.

The Netherlands, or Nederland in Dutch, means “lower lands,” because they were flatlands not much above sea level. Some parts were even below sea level but kept dry by walls called “dijks” (“dikes” in English). The provinces of the Netherlands that broke away in the 1560s and 1570s were in the north and became the Republic of the United Netherlands, usually referred to as the Dutch Republic by historians. Today it is called the Kingdom of The Netherlands (sometimes nicknamed “Holland,” just to confuse us). They speak Dutch, a Germanic language. The Southern Netherlands—the part where Brouwer lived—stayed under Habsburg control, and was divided between Flemings in the north (who speak Dutch) and Walloons in the south (who speak French). Later the entire southern Netherlands would become the country of Belgium.

There are actually three famous Defenestrations of Prague. The first took place in 1419 when a group of angry Hussites (they were the prequel to the Protestants) throw some city councilors out the window (they all died). The third was in 1948 when Czech Foreign Minister Jan Masaryk fell to his death on the pavement below his office. It was widely suspected (but never proven) that the Soviet Union, which was forcing Czechoslovakia to become a Communist country, had ordered him killed.

Love this! Reading about historical events through the eyes of art, artists, or average humans is ALWAYS fantastic!

Great stuff. Back when I used to teach American military history I would pair Callot's "Miseries of War" series with the descriptions of the Anglo-Powhatan wars.

More recently I've come to a greater appreciation of the eighteenth century artwork of Hubert Robert - in some ways he seems to have prefigured the Hudson River School.