Oppenheimer: A reaction

Unavoidable minor spoilers ahead, but I’ll try to be reasonably vague.

Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer is layered (like every Nolan film?), slicing its story into three timelines: a conventional chronology from the pre-war years through the building of the bomb (or “the gadget,” its security nickname); a 1954 hearing on renewing Oppenheimer’s security clearance, fired by Cold War fears of the Soviet Union and given fuel by Oppenheimer’s life-long sympathy with left-wing causes; and a final hearing in 1959, this one for Lewis Strauss (Robert Downey Jr.), who had been the head of the Atomic Energy Commission. All three timelines allow for flashbacks and interconnections, and so ideas that were fuzzy early on gradually become clearer as Nolan shines light on them from different angles.

And yet nothing becomes completely clear, and that is a blessing. At one point, Oppenheimer is called a sphinx, “no one knows what you think,” and, thanks to Nolan and Cillian Murphy’s brilliant acting, this remains both true and untrue. We spend three hours with Oppenheimer, and we both feel we know him and yet can’t be quite sure what’s going on behind those inhuman blue eyes.1

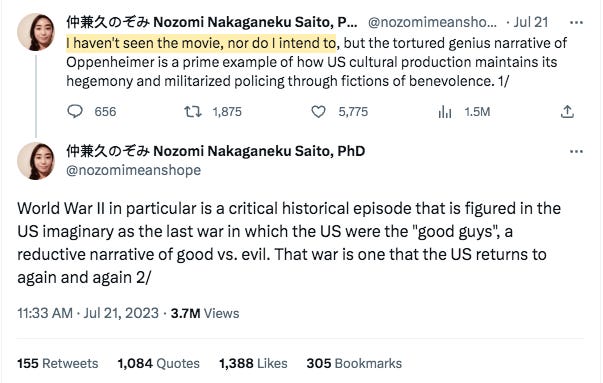

This has frustrated Twitter reviewers who want the film to Say Something Important About Racism or Colonialism or God Knows What. Or some of them already know what the film is about and so don’t have to see it (but need to tell us why).

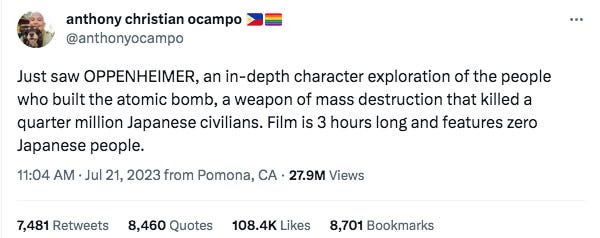

Another Twitteratti got one hundred thousand likes for complaining that a film set in America and Europe had no Japanese people!2

This style of commentary stems from a belief that art should be virtuous and have a message that fits in with current mores. In the eyes of scolds, art becomes “not a site of numerous meanings but that which contains a single blunt message,” and “its value lies not in itself but in its moral or political content.”3 So the left gets mad that Oppenheimer doesn’t attack racism, while the right complains that Barbie is horrible because it mentions the patriarchy. These approaches to cinema turn everything into partisan ammunition, and the question stops being, “Is it beautiful? Does it move me?” and becomes the sanctimonious, “Does it say the right things in the right way.”

Nolan isn’t bowing to that kind of sterile didacticism. He wants to look at the world at the dawn of the atomic era through the eyes of one of its central figures. He’s not trying to preach a sermon on atomic horror or American arrogance (although both are confronted). He has lots to communicate but leaves us free to decide for ourselves whether or not he’s right (and to argue about what exactly he was saying!).

Nolan’s Oppenheimer is a genius physicist who likes neither math nor experiments. His behavior is alienating, his personal life troubling, and yet people are drawn to and admire him. He is an idealist who supports the rebels in the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) but finds Communism too flawed to join the Party—although his friendships with many who did join, including his future wife Kitty (Emily Blunt), would cause him much later trouble.

Early in the film, Oppenheimer has a critical meeting with General Leslie Groves (Matt Damon), who decides that “Oppie” is the best man to lead the Manhattan Project, the giant government program to build the first atomic bomb. The meeting between the physicist and the military officer shows us two intelligent, ambitious men sizing each other up and deciding they just might do great things together. One of the joys of Oppenheimer is showing us smart people talking about serious things without babysitting the audience.

Making the bomb was a huge endeavor (over a hundred thousand workers), and Nolan conveys well the scale and uncertainty of an operation resting heavily on a shaky foundation of theory. All the big brains thought the bomb was possible, but nobody knew exactly what would happen when that final button was pressed. (What does happen? How does Nolan show that successful Trinity4 test? I won’t spoil the scene, but it lives up to the hype.)

Then there were the ethical questions. Is it acceptable to try and build something that will be used to slaughter tens of thousands in an instant, many of them civilians? Nolan shows us that much of the drive to build a bomb started with the fear that Germans would get there first, but when it became clear that wasn’t going to happen, many scientists had second thoughts. The arguments for and against dropping two bombs on Japan (it would save countless lives if Japan fought on; it was unnecessary if they were going to surrender anyway) are laid out, but they began to seem almost pointless because once America had the thing, it became inevitable she would use it. There was a petition organized by Leo Szilard (Máté Haumann) to get President Truman (Gary Oldman) to warn the Japanese so that they could surrender—this is briefly touched on in the film—but Truman wasn’t going to be stopped by “cry-baby” scientists.

Adding another layer of moral ambiguity, the Manhattan Project was supposed to be secret from America’s wartime ally, the Soviet Union. Stalin was only told after the Trinity test that America had a “new weapon of unusual destructive force.” Some of the scientists working for the Manhattan Project were sympathetic to Communist ideas, a few of them had even been Party members, and there was a feeling that perhaps the Soviets should be told. Of course, Stalin already knew about America’s big bomb. One scientist, Klaus Fuchs (Christopher Denham), was a key player in funneling atomic secrets to the Soviets (he was arrested in 1950 and served nine years in a British prison).

After the war, when everyone knew what the bomb could do, some of the scientists who had built the thing, including Oppenheimer, were inspired to push for restraint in developing the new and more nightmarish thermonuclear (hydrogen) bomb. Others saw the H-Bomb as necessary in the face of the Soviet threat.

All these layers, the intertwined storylines, the flashbacks create a mosaic of questions half-answered around Oppenheimer, America, Communism, and the bomb. Was Oppenheimer right to lead the project that created so much horror? Was America right to drop the bomb? Nolan has his biases but gives these debates air to breathe. He treats the audience like adults who can make up their own minds. Maybe he’s not sure in the same way that Oppenheimer wasn’t sure.

Does this movie answer all the questions surrounding the bomb? Of course not; no film could.5 Is it a great movie? I think so. There were a few heavy-handed moments, but they didn’t lessen my enjoyment. The acting (with lots of big names!) was stellar. I want to see it again, and that’s pretty telling. I’m also cheering for it. It’s heartening to see a serious film on a grim topic, a film for adults who understand moral ambiguity, garner so much positive press and audience response.6

Yes, I checked: Oppenheimer’s eyes were blue too. “It’s a real problem when you’re doing scene work with Cillian. Sometimes you find yourself just swimming in his eyes,” Matt Damon told People magazine.

Which is not quite true.

From “The Great Debasement,” Tablet magazine, May 2022.

Oppenheimer chose the codename “Trinity,” supposedly inspired by the poems of John Donne (1571-1631).

Immediately after watching Oppenheimer, I downloaded the book upon which it is based, American Prometheus by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherman.

The critic and audience scores on Rotten Tomatoes were both 94% as of July 25. Its box office was $82 million on its opening weekend ( New York Times). Very impressive for a three-hour biopic and well on the way to making back its $100 million price tag.

Good stuff. This sort of demand that art be moral/woke to a "T" ran hot in the late 2010s, but I think people are tired of it now. There's way more pushback and mockery of the silly, scoldy tweets than there was before. The vibe has shifted.

Behold! We find the criticism of not showing the Japanese suffering to be rather wan. Because instead, he shows American citizens suffering in the exact same way. Which brings home the suffering in a way that won't work for people who "don't care" about the WWII-era Japanese.

We also were impressed by the subtle narrative gadget that plays out through the two timelines. "Fission" is specifically about the creation of the atomic bomb. Narratively, the story brings everyone together, there's a huge explosion and then they all split apart. "Fusion" is about the creation of the H-Bomb, which is a weapon where an atomic explosion pushes in on (otherwise stable) heavy hydrogen, causing it to fuse together, creating an even bigger explosion. Narratively, the story shows us how the very stable Strauss is confronted by atomic scientists providing explosive testimony, causing a catastrophic result.