NPR and our lost trust in media

We don’t trust the media.

“What do you mean ‘we’?” you respond, “I trust the media!”

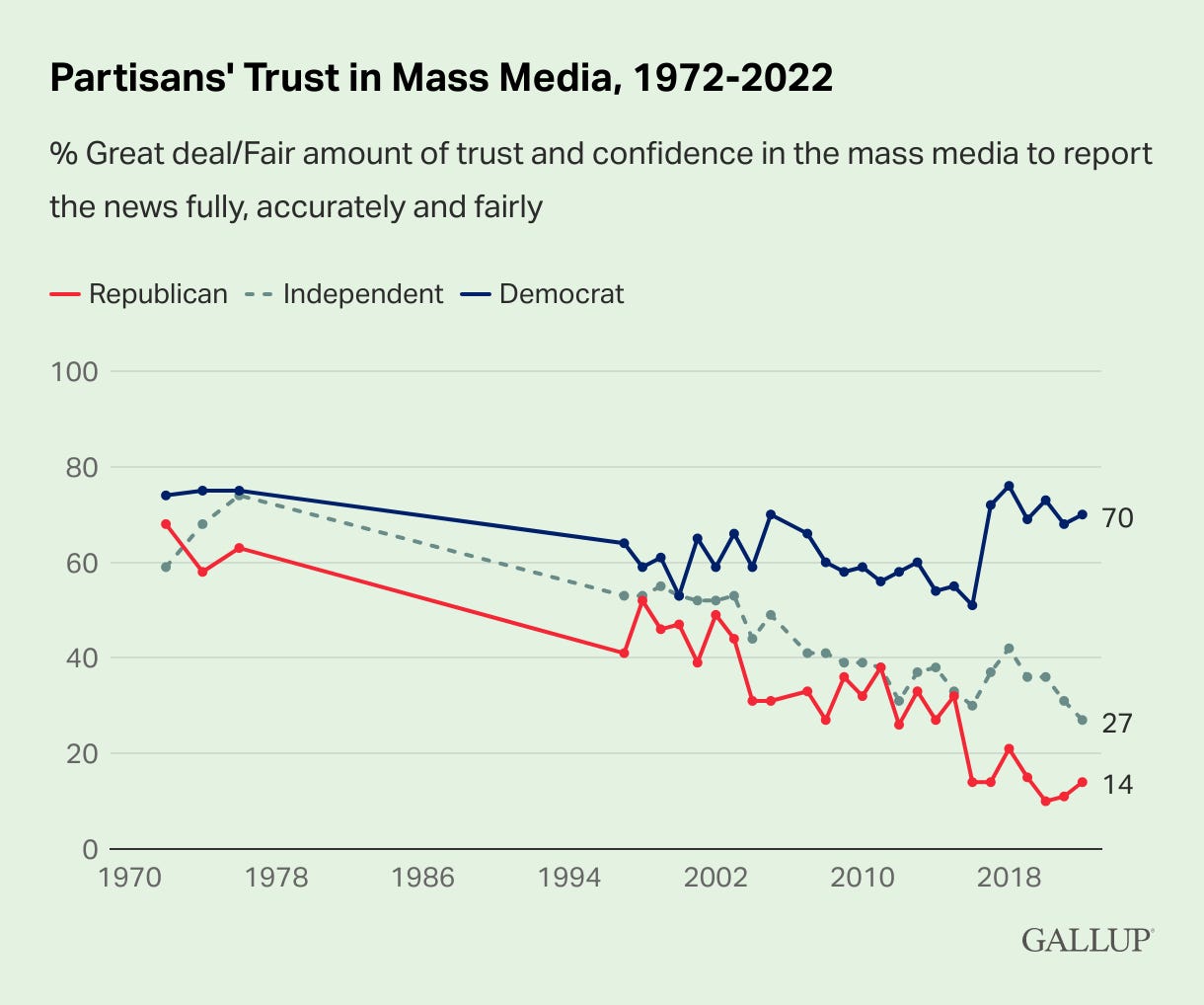

Fine, but you’re outnumbered. Gallup says trust in media has been steadily dropping since the rocking 1970s when the Washington Post brought down the corrupt presidency of Richard Nixon, with a little help from Walter Cronkite over at CBS News. These days, only about one-third of the country trusts those ink-stained wretches.1

If you’re a Democrat, this might come as a shock. Everyone you know trusts the media! That’s because the media skews left, and you’re left, and what’s wrong with the media again? In these strange times, when we buy our pillows based on partisanship, how could we not view the media through red and blue lenses? Democrats’ trust in media is at 70%, close to the 1970s heyday, but Republicans and Independents have lost the faith, and that’s a lot of folks. (In Gallup’s most recent survey, Republicans made up 25% of the country, Independents 44%, and Democrats 27%.2)

I’m a Democrat, but I’m one of those whose trust in media has fallen, and a recent National Public Radio (NPR) story explains some of my lost faith.

NPR is responding to the recent Supreme Court decision—Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard—which ended affirmative action. The plaintiffs claimed that Harvard's admissions policies had discriminated against Asian students. The NPR article rejects that claim and makes the case that the real goal of the plaintiffs was to help white students.

"Asians were standing in as proxies for white students," says Jeff Chang, a writer and activist who has long fought for affirmative action. "That's essentially the strategy that Ed Blum used."

In NPR’s telling, Asians were tools of whites, with no opinions of their own. As writer and podcaster, Katie Herzog pointed out, there are no Asian opponents of affirmative action quoted in the NPR piece. Every single voice was singing affirmative action’s benefits for Asians.3

The most amazing—and laughable—paragraph in NPR’s article quotes Professor OiYan Poon,4 who bald-facedly asserts there was no anti-Asian discrimination in admissions at Harvard.

"I've been pouring over the data for years," she says — including the admissions data of Harvard before the court in one of the case that just ended affirmative action. "There is no evidence that there's a practice of anti-Asian discrimination."

“No evidence.” The illusion of anti-Asian discrimination was created by “conservative political forces.”

That NPR could quote this professor without any pushback against her obviously untrue statement is journalistic malpractice. The fact that Asians were discriminated against was discussed even in other liberal media outlets.

Jay Caspian Kang, in a recent article for The New Yorker, writes:

The evidence the plaintiffs had amassed that Harvard, in particular, discriminated against Asian applicants through a bizarre and unacceptable “personal rating” system is overwhelming.

The New York Times covered this back in 2018:

Harvard consistently rated Asian-American applicants lower than others on traits like “positive personality,” likability, courage, kindness and being “widely respected,” according to an analysis of more than 160,000 student records filed Friday by a group representing Asian-American students in a lawsuit against the university.

Asian-Americans scored higher than applicants of any other racial or ethnic group on admissions measures like test scores, grades and extracurricular activities, according to the analysis commissioned by a group that opposes all race-based admissions criteria. But the students’ personal ratings significantly dragged down their chances of being admitted, the analysis found.

More recently, Jonathan Chait at New York Magazine gave some numbers:

Harvard itself found in a 2013 internal study that, if it admitted applicants solely on the basis of academic merit, its share of Asian American students would explode from 19 percent to 43 percent.

According to Harvard’s own internal study, if only academics were used, Asian students would double their numbers at Harvard. And white students were not the main group negatively affected by affirmative action. The bulk of the increase in black and Hispanic students was achieved by reducing the number of Asians who would otherwise have been admitted.

If Harvard had kept its admissions process the same in all aspects except for eliminating racial preferences, it would have admitted 491 more whites and 799 more Asians across the sample of applicants they examined. To put those figures in context, they find affirmative action led to the rejection of 28% of Asian applicants to Harvard who would have been admitted without the policy; for white applicants, the number is only 15%.

”Affirmative Action Has Been Specifically Discriminatory Against Asians,” Josh Barro, July 12, 2023.

And yet NPR can quote Professor Poon saying:

"It's really tapping into fear with zero evidence."

Zero evidence? Zero?!?

Why did NPR distort the truth so blatantly? How could they completely ignore Asian people’s agency? Because doing so fits in with a worldview that is popular in certain corners of the left, namely that everything in America is characterized by systemic oppression and white people are the ultimate villains behind most of what goes wrong. For NPR writers, that worldview is the truth, never mind any inconvenient facts. They believe this so firmly that I’m not at all sure they know they’re lying.5

America does have a history of racism, and some of that lingers today, but to see everything through the lens of white oppression is to garishly distort reality. When mainstream journals publish articles like “America's national parks face existential crisis over race,” “The knitting community is reckoning with racism,” “White supremacy, with a tan,” and “Straight Black Men Are the White People of Black People,” you’ve entered into parody land.

The NPR article is filled with this kind of language.

This myth of affirmative action being harmful to Asian Americans is creating a deliberate racial wedge between communities of color. It's ultimately rooted in anti-Blackness.

It reads like the caricature of a Critical Studies professor lecturing at Oberlin.

The promise of proximity to whiteness and power has radicalized some Asian Americans on the right.

This worldview insists that everything revolves around white people, and Asian students and parents can only be puppets of whiteness, unable to oppose progressive ideas for their own reasons.

In reality land, most Asian Americans, like most Americans, and unlike most professors of Intersectional Studies, have long tended to oppose using race in college admissions. I say “tended” because a lot depends on what language is used in poll questions. A 2022 Pew survey reported that a modest majority of Asians who had heard of affirmative action thought it was a good thing (53%), but most Asians also thought that colleges should not “consider race or ethnicity in admissions decisions” (76%). It seems Asian Americans like the idea of helping make colleges more diverse but dislike the idea of using race to make that happen.

If all I knew was NPR’s article, I might come away with the impression that most Asian people were united in favor of using race in college admissions, except for the small number who had been duped by clever whites. After all, I’d been given quotes from a roster of “experts” who had told me this was the only reasonable point of view. If you can’t trust a Director of the Race and Intersectional Studies for Educational Equity Center, who can you trust?

And, of course, NPR was hardly alone. Here’s Xochitl Gonzalez in The Atlantic saying that

The cases relied on the cynical recruitment of a handful [emphasis added] of aggrieved Asian American plaintiffs.

If I were a progressive trapped in left-wing echo chambers, I might find these articles (and others like them) reassuring. They would confirm all my assumptions. Affirmative action is good, and only white racists think otherwise.

If, however, I had come across any other information. Gallup poll numbers, Pew’s reports, Jay Kaspian Kang and others’ reporting, I would realize that NPR had lied to me. If I saw too many of those lies in NPR and elsewhere, how could it help but diminish my trust in the media?

And it has. I’ve read too damn many articles that left facts out, downplayed negative evidence, or just outright pushed absurdity. They weren’t all as bad as NPR’s tissue of nonsense, but their collective weight eroded my trust. All too often, it felt like they were prioritizing making a case for progressive views over the truth. It makes me think of Wesley Lowery’s 2020 call for “moral clarity” over mere “neutral objectivity.”

I still remember my shock at reading this morally clear paragraph in a 2020 New York Times article covering a controversy over whether or not to paint “Black Lives Matter” on a Catskill, New York street.

The proposal didn’t seem like too much of an ask; in the weeks since George Floyd was killed by the police in Minneapolis, the phrase has been painted on streets from Washington, D.C., to Charlotte, N.C., and, on Thursday, even in front of Trump Tower in Manhattan.

Those first words, “The proposal didn’t seem like too much of an ask,” were clearly taking a side in the controversy. It may seem trivial, but it’s something reporters should never do. The reporter was, by implication, chastising those resisting the street art for saying “no” to such a small request. It’s fine to have that opinion, but it shouldn’t be in a news article. Once you start taking sides, you’re making a case, and like any good lawyer, you may leave out or downplay something that doesn’t advance your case. Prioritizing case-making is what led NPR to leave out strong evidence that affirmative action might be bad for Asian students.

It was too many moments like that which made me distrust mainstream media in a way I never had before. These days I’m always wondering if they’ve left out some key bit of information because they think it would undercut their preferred narratives. This is unfortunate. I can’t fact-check every article I read, so instead, I just trust them all a bit less.

I haven’t fallen in with the “it’s all lies” crowd. I think mainstream media often does excellent reporting, but on some topics, particularly those around hot-button issues like race, they have become less reliable.

I’ve seen signs of improvement—especially at the New York Times—but these days, I read articles on certain topics with a more skeptical eye. And that’s me, a liberal Democrat. How do you think this playing fast and loose with the facts affects more conservative readers? Gallup’s poll numbers answer that question.

I know nobody is using ink anymore, but I’m old, let me pretend. I miss reading the physical copy of the New York Times on Sunday mornings and getting my hands lightly stained by the ink residue.

Obviously, a few people choose other options. Libertarians or Rosicruicans, perhaps.

Katie and Jesse Singal covered this story at great length in their podcast, Blocked and Reported.

NPR lists Dr. Poon as a “professor at Colorado State,” but her bio says she was the “former director of the Race & Intersectional Studies for Educational Equity (RISE) Center at Colorado State University,” which makes sense. She sounds very intersectional.

“Two and two are four.” “Sometimes, Winston. Sometimes they are five. Sometimes they are three. Sometimes they are all of them at once.”

If I were to guess, I'd say that Professor Poon might not see the discrimination against Asians; if your main goal is equity, you might be tempted to define a discriminatory action as an action that disadvantages underrepresented groups. Under that definition, there is no discrimination against Asians.

This revised definition makes little sense to me, but it might be the standard definition in intersectional circles.

At first, I was going to say something about this being a bad effort at steelmanning the argument that the press hasn’t lost public trust for justifiable reasons, because it uses NPR as an easy punching bag. (I personally have hated them for a couple decades at least; the last positive memories I have of them date back to the time of Andrei Codrescu’s “The Hole In The Flag”.) But reflecting on it, this is fair, if a bit cartoonish, given NPR distills all the faults of the media for its noisy audience of totebag recipients.