Free Speech is not a Luxury

It's our defense against error.

"If all mankind minus one, were of one opinion, and only one person were of the contrary opinion, mankind would be no more justified in silencing that one person, than he, if he had the power, would be justified in silencing mankind."

— John Stuart Mill, On Liberty (1859)

Mill’s ringing call for individual freedom seems to establish it as a natural right in the tradition of John Locke. Mill, however, was a utilitarian1 and his defense of freedom is grounded in the idea that freedom is useful. Allowing freedom, especially freedom of thought and speech, makes society more successful, happier.

Many today seem to view free speech as an upscale luxury—an Apple Watch or a bidet—sometimes nice to have, but not really necessary. Other issues take priority: preventing harm to marginalized groups or silencing critical race theory in the classroom (depending on your ideological bent). This luxury framing ignores that free speech, even speech we loathe—maybe especially speech we loathe—is incredibly useful.

Some of this may be the fault of free speech advocates, who are often quick to assert the right to free speech without spending much time explaining why the free flow of ideas is good for us all.

Barack Obama

Back in 2015, attacks on speech from the left were becoming more common on campuses across the country. Students and professors were saying that preventing harm (caused by hurtful words or ideas) was sometimes more important than free speech. It’s in this context that President Barack Obama answered a question at a Town Hall on “College Access and Affordability” (Des Moines, Sept 14, 2015).

A student named Abba asked:

a candidate has said that they want to cut government spending to politically biased colleges, and I was wondering if, say, that would hurt the education system

Obama gave a longish reply outlining very clearly his position on the importance of free speech.

Look, the purpose of college is not just, as I said before, to transmit skills. It’s also to widen your horizons; to make you a better citizen; to help you to evaluate information; to help you make your way through the world; to help you be more creative. The way to do that is to create a space where a lot of ideas are presented and collide, and people are having arguments, and people are testing each other’s theories, and over time, people learn from each other, because they’re getting out of their own narrow point of view and having a broader point of view.

In other words, you become better at processing knowledge, and therefore more knowledgable, if you are forced to test your ideas against the arguments of those who disagree with you.

It was in college that Obama…

started testing my own assumptions. And sometimes I changed my mind. Sometimes I realized, you know what, maybe I’ve been too narrow-minded. Maybe I didn’t take this into account. Maybe I should see this person’s perspective

Obama now zeroes in on those progressives who don’t want to hear from harmful ideas.

I’ve heard I've of some college campuses where they don’t want to have a guest speaker who is too conservative. Or they don’t want to read a book if it has language that is offensive to African Americans, or somehow sends a demeaning signal towards women. And I’ve got to tell you, I don’t agree with that either. I don’t agree that you, when you become students at colleges, have to be coddled and protected from different points of views. [applause]

Obama follows up:

you shouldn’t silence [speakers] by saying, you can’t come because I’m too sensitive to hear what you have to say. That’s not the way we learn, either.

Obama does not frame speech as a luxury. Speech is “the way we learn.” Free speech is a necessity. He’s not against “coddling” because it makes students weak, he’s against coddling because it stands in the way of learning.

The whole question and answer is at the 40-minute mark:

Free debate—challenging the views of others and allowing our own to be challenged—facilitates discovering the truth. Without it, we remain prone to error and not as smart as we would be otherwise.

John Stuart Mill

(John Stuart Mill, c1858. Photograph: Getty Images)

Obama’s answer outlined how this road to truth works, but 156 years earlier, philosopher John Stuart Mill went into Victorian-era-prose detail.

The peculiar evil of silencing the expression of an opinion is, that it is robbing the human race; posterity as well as the existing generation; those who dissent from the opinion, still more than those who hold it. If the opinion is right, they are deprived of the opportunity of exchanging error for truth: if wrong, they lose, what is almost as great a benefit, the clearer perception and livelier impression of truth, produced by its collision with error.

Mill is arguing we have two ways of losing when we silence other voices:

First, maybe they are right and we’re wrong. “I know you think that slavery is evil but I don’t want to hear your ideas and so I’ll burn your printing press, and maybe shoot you as a bonus.” (In 1837, an Illinois mob attacked a warehouse where abolitionist Elijah Parish Lovejoy stored his printing press. Lovejoy and his allies held the mob at bay, killing one participant, but when Lovejoy opened the door to see if the mob had departed, he was shot dead.) Silencing people robs us of the chance of replacing bad ideas with better ones.

To refuse a hearing to an opinion, because they are sure that it is false, is to assume that their certainty is the same thing as absolute certainty [emphasis is Mill’s]

As certain as we may feel about gun control or climate change, our personal certainty is not the same as absolute objective certainty. In their own time, defenders of slavery were absolutely certain that they were correct.

Second, even if we’re right, we’ll have a clearer idea of why we’re right if we are forced to defend our ideas. I am pro-choice. My pro-choice arguments are stronger because I listen to pro-life opponents. By attacking my ideas (“what about late-term abortions?”) they force me to think harder and come up with better defenses (or even change my mind). We need this. We are not good at seeing the flaws in our own arguments.2

Mill says if we don’t permit our positions to be challenged, they become essentially religious texts, oft-repeated but devoid of real meaning.

However unwillingly a person who has a strong opinion may admit the possibility that his opinion may be false, he ought to be moved by the consideration that however true it may be, if it is not fully, frequently, and fearlessly discussed, it will be held as a dead dogma, not a living truth.

You can chant:

America is the best!

America is the best!

America is the best!

But when asked “why?” your answer will only be a bellicose “Because America is the best!” Slogans become meaningless without being vigorously and regularly defended, as evidenced by a classroom full of 3rd graders reciting the Pledge of Allegiance in a chorus of dull monotones.

deprived of its vital effect on the character and conduct: the dogma becoming a mere formal profession

Yes, fine, that may have been the case in the past, but today is different, we are different. Today the things we know to be true really are true and so should not be challenged. And, Mill replies, this is what people have always thought, people who we now know to be wrong.

Nor is his faith in this collective authority at all shaken by his being aware that other ages, countries, sects, churches, classes, and parties have thought, and even now think, the exact reverse. He devolves upon his own world the responsibility of being in the right against the dissentient worlds of other people; and it never troubles him that mere accident has decided which of these numerous worlds is the object of his reliance, and that the same causes which make him a Churchman in London, would have made him a Buddhist or a Confucian in Pekin. Yet it is as evident in itself as any amount of argument can make it, that ages are no more infallible than individuals; every age having held many opinions which subsequent ages have deemed not only false but absurd; and it is as certain that many opinions, now general, will be rejected by future ages, as it is that many, once general, are rejected by the present.

This is the idea that makes heads explode. We know people used to be wrong. We understand that we must sometimes also be wrong. We just can’t wrap our brains around the idea that our particular views on a particular topic (Trump, transgender rights, cancel culture, abortion) could possibly be wrong. We know we’re right. Just like all the wrong people throughout history.

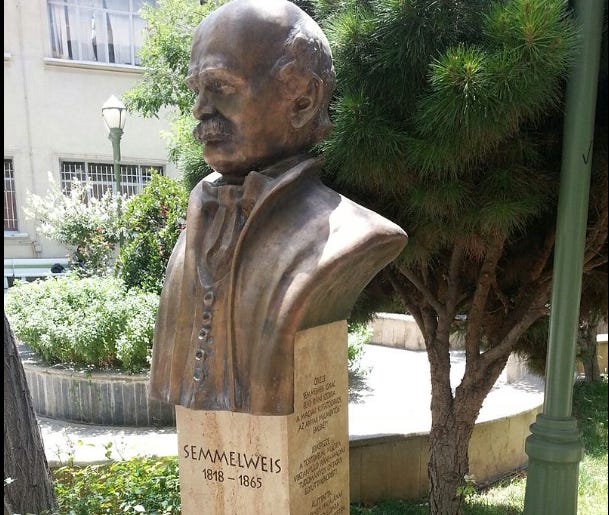

In the 1840s, Ignaz Semmelweis started making doctors in his Vienna clinic wash their hands, greatly reducing the clinic’s mortality rate. His push to get other doctors to start handwashing, however, met with near universal hostility (Invisible particles that make people sick? Superstitious nonsense!) and this seems to have gradually driven him a bit mad. Semmelweiss was eventually forcibly committed to a mental hospital where, after being beaten, he died in 1865. The doctors of Semmelweiss’s time knew they were right, and yet they were wrong.

(Ignaz Semmelweis statue at the University of Tehran.)

In 1954, Alan Turing, a man who had helped break the German Enigma code and thereby significantly contributed to winning World War Two, committed suicide because he had been forced to accept chemical castration as a punishment for being gay. Turing’s contemporaries knew homosexuality was immoral, and yet they were wrong.

Humans are wrong again and again and again. It is hubris if we think that our time, our political party, or our culture war ideology is somehow immune to this truth. We should have it tattooed on humanity’s collective forehead: SOMETIMES WE’RE WRONG! Our best chance of being less wrong is to allow “correct” views to be challenged and “incorrect” views to be defended.

Complete liberty of contradicting and disproving our opinion, is the very condition which justifies us in assuming its truth for purposes of action; and on no other terms can a being with human faculties have any rational assurance of being right.

The enemy of free speech is us

Who is stopping us from speaking and debating freely? Mostly ourselves.

In America, the founding fathers (after fierce debate) added the Bill of Rights, including the much lauded 1st Amendment:

Despite the laws and declarations3 defending it, free speech is never especially popular. Or rather, we like it when our side speaks freely, but not so much when those other idiots spew garbage.

(From Free Speech, by Jacob Mchangama)

Not long after that Bill of Rights was ratified, a Federalist-dominated Congress, furious at criticism by political opponents, passed the Sedition Act (1798) which made it illegal to “write, print, utter or publish” “any false, scandalous and malicious writing or writings against the government of the United States, or either house of the Congress of the United States, or the President of the United States.” Writers and editors were arrested and charged under the act, including Benjamin Bache, who called President Adams the “blind, bald, crippled, toothless, querulous Adams.” (And you thought cable news was bad.) Anger at the Sedition Act helped to win Thomas Jefferson the presidency in 1800 and the act was allowed to expire.

In 1971, Daniel Ellsberg leaked the Pentagon Papers to the New York Times and the Washington Post. The Papers—officially called Report of the Office of the Secretary of Defense Vietnam Task Force—outlined the course of the Vietnam War, detailing its many failures, and showing that the U.S. government had been lying to the American people from the beginning. Both newspapers (and later others) began publishing articles based on the report and the Nixon administration tried to stop them on national security grounds. On June 30, 1971, the Supreme Court ruled 6-3 that the government did not have the right to stop publication. Justice Hugo Black wrote, “Only a free and unrestrained press can effectively expose deception in government.”

Mill, however, was not only, or even primarily concerned about government censorship. He also feared the “tyranny of the majority,” not by laws (although that would also be bad) but through social pressure.

Like other tyrannies, the tyranny of the majority was at first, and is still vulgarly, held in dread, chiefly as operating through the acts of the public authorities. But reflecting persons perceived that when society is itself the tyrant—society collectively, over the separate individuals who compose it—its means of tyrannising are not restricted to the acts which it may do by the hands of its political functionaries. Society can and does execute its own mandates: and if it issues wrong mandates instead of right, or any mandates at all in things with which it ought not to meddle, it practises a social tyranny more formidable than many kinds of political oppression, since, though not usually upheld by such extreme penalties, it leaves fewer means of escape, penetrating much more deeply into the details of life, and enslaving the soul itself.

“Enslaving the soul itself,” is grimly poetic. Fitting into society, having the good opinion of our fellow humans, and not risking friendships, employment, or public shunning, these are all strong incentives to not step out of line. Mill knew the pain of public criticism firsthand. He was an advocate for women’s rights (he wrote The Subjection of Women in 1869) and received regular ridicule as a result.

(Mill portrayed in women’s clothes by satirical British magazines.)

Today people hurl labels like racist, transphobe, pedophile, and groomer, in an attempt to silence speech they think shouldn’t be heard. They justify their actions as necessary and good—I am silencing bad people!—but they are going against Mill’s reminder that their certainty is not the same as absolute certainty.

When Christina Pushaw, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis’s press secretary, said anyone opposing DeSantis’s new “Don’t Say Gay” law (another questionable label) was probably a groomer or supporter of groomers, she was using a horrific label in an attempt to intimidate those who might otherwise speak up.

I don’t wish to exaggerate today’s restrictions on speech. I live in a remarkably free time in a remarkably free country. The United States is blessed with a First Amendment that protects me from attempts by the government to limit my speech. Other western countries have their own robust speech traditions. Whether I’m in New York, Paris, or Melbourne, I can yell that the government is filled with thieves and it’s time to vote the bastards out and not fear arrest or legal retribution. Government censorship, however, is not the only way that speech can be suppressed.

A culture of free speech

How to protect speech from governmental and non-governmental threats? Mill argued for building a culture that respected original thinkers. This, Mill admits, is not easy. He said people claimed to respect genius, but true genius was too alienating, too different.

People think genius a fine thing if it enables a man to write an exciting poem, or paint a picture. But in its true sense, that of originality in thought and action, though no one says that it is not a thing to be admired, nearly all, at heart, think that they can do very well without it. Unhappily this is too natural to be wondered at. Originality is the one thing which unoriginal minds cannot feel the use of. They cannot see what it is to do for them: how should they? If they could see what it would do for them, it would not be originality.

Mill wants a society that encourages originality in thought.

I agree.

We should make it a point of honor to defend those whose ideas we dislike. “I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it.” (The quote is often attributed to Voltaire but it was actually penned by a writer describing her interpretation of Voltaire’s outlook.) This is the attitude that led the American Civil Liberties Union to defend the right of neo-Nazis to march through Skokie Illinois in 1977.

In his essay “Why Defend Freedom of Icky Speech,” Neil Gaiman wrote, “If you accept—and I do—that freedom of speech is important, then you are going to have to defend the indefensible. That means you are going to be defending the right of people to read, or to write, or to say, what you don't say or like or want said…because if you don't stand up for the stuff you don't like, when they come for the stuff you do like, you've already lost.” (Gaiman was defending free speech for artistic reasons; a reminder that Mill’s usefulness defense is not the only argument for defending freedom of expression.)

This doesn’t mean we shouldn’t criticize ideas we think are bad. Just be sure you are attacking the ideas rather than trying to silence them. “I think your article is bad and this is why…” is the way. “That article was evil and your newspaper shouldn’t have published it” is not the way. If you want to cancel the appearance of a provocative speaker or an edgy comedian, neither Mill nor Obama would approve, because silencing speech we don’t like is not how we learn.

And remember Mill’s other point: Even if you’re sure an idea is bad, it usually does you and society good to be exposed to it. Good ideas need to be regularly defended from bad ideas by arguments, not censorship. This makes the good ideas stronger.

Should there be any limits on speech? Of course. Laws against direct incitements to violence are necessary. Teacher’s classroom speech can be regulated (“Class, let us all pray”) in a way their public speech shouldn’t be. Colleges and newspapers should stretch to allow different views, but some limits are reasonable. (You can skip inviting literal Nazis to speak, although you should still read their books.) Content moderation is not oppression. A knitting website might reasonably keep insulting posts off their discussion pages. Outlining what limits speech should have, however, would triple the length of this piece. I’ll simply say that if we err it should be in the direction of allowing speech that we hate.

Finally, have a bit of humility. Unless you truly think you’re perfect, you must be wrong some of the time. This is why society needs vigorous public debate.4

Postscript: In the spirit of my piece, I will add one final thought: I might be wrong. Obama, Mill, and I all think that free debate, exposure to troubling or even stupid ideas, is the way we find our errors and make a better society. What if we’re wrong? I can’t help but think of today’s China. Speech is rigorously suppressed and yet China is a prosperous thriving society. I wouldn’t want to live under their speech restrictions but they don’t seem to hamper China’s efficiency. I suspect that in the long run, China’s policy of repression will limit its growth, but I might be wrong.

Although Mill wrote an entire book devoted to explaining utilitarianism (Utilitarianism, 1863), some have argued that he stretched utilitarianism into something not entirely utilitarian. He, of course, disagreed.

Or weaknesses in our own essays.

Article 19 of the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights states: “Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.”

My “we might be wrong” mantra makes me think of the LessWrong community, but I don’t know enough about them to comment further.

Very nice. As I understand these things, US law protects speech to a greater degree than most democracies. Also, I'd be curious as to your thoughts on free speech in non-government entities, e.g. the NFL and social media.

Our right to free speech extends beyond opinion. If Alex Jones hadn't caused verifiable harm, his lies (not opinions) broadcast publicly would be legal. Ditto for chips in vaccines. I like John Perry Barlow's formulation of the principle of charity, "Never assume the motives of others are, to them, less noble than yours are to you", though with clear verifiable lies, I find I must make such an assumption.

The dividing line between subjective opinion and objective fact isn't always clear. On occasions where it is, it is still protected. And that creates problems and often societal harm. What say you and Milton about that?

Very excellent. Ends Justify Means is more appealing to most people than A Nation of Laws. So, we are always tempted to pass laws to curtail "bad" speech. The 2024 book "The Indispensable Right: Free Speech in an Age of Rage" by Jonathan Turley is a thorough exploration of the history and application of the First Amendment. [I read the first several chapters and then skipped forward to the conclusion: https://www.amazon.com/Indispensable-Right-Free-Speech-Rage/dp/1668047047/] Thank you!