Extreme Speech

In the beginning, there was a tweet, and it was bad.

And then it got worse.

Professor Uju Anya, a linguist at Carnegie Mellon University, was not alone in gloating over the Queen’s death (Irish Twitter was particularly bumptious), but her remarks seemed particularly cruel. Angry fans of the Queen piled on her, Twitter took the unusual step of deleting her initial tweet, and then the professor’s own university weighed in:

Was the reaction to Anya’s tweets excessive or did she deserve more?

Ugly speech is good

First, to all the “well actually” pedants in all the threads who are panting to point out that her First Amendment rights were not being violated, yes, we know. Professor Anya had every legal right to make her tweets. She won’t be dragged away in handcuffs.

In democracies, however, the most common threat to free speech isn’t the government, it’s your fellow citizens, whether acting through social pressure (stop saying those things or your friends will abandon you) or threatening livelihoods (stop saying those things or we’ll fire you).

When society is itself the tyrant—society collectively, over the separate individuals who compose it—its means of tyrannising are not restricted to the acts which it may do by the hands of its political functionaries…it leaves fewer means of escape, penetrating much more deeply into the details of life, and enslaving the soul itself.

— John Stuart Mill, On Liberty (1859)

Free speech is always worth defending. (Read my essay, “Free Speech is not a Luxury”). Without some protection from both government and social pressure, new ideas that can improve our world are smothered before they can spread. A culture of free speech protects speech that nobody likes because history has demonstrated many times that widely reviled ideas (slavery is wrong, women deserve the vote) can eventually become recognized as necessary and virtuous. We protect bad ideas for many reasons but one of the most important is sometimes we find out much later they weren’t actually bad.

Still, even free speech advocates like Mill admit that some restrictions on speech are reasonable. Child porn is out. No directly inciting mob violence. Libel, carefully defined, is also unacceptable. Professor Anya crossed none of those lines.

Anya called Queen Elizabeth the “monarch of a thieving raping genocidal empire.” Accuracy isn’t necessary for speech to be protected but this seems defensible—which is not the same as saying I completely agree. The British Empire stole large chunks of Asia, Africa, and the Americas from their inhabitants. When Elizabeth became queen, the British still controlled Sudan, Ghana, Somalia, Nigeria, Uganda, Kenya, Zambia, and Botswana (and many more), and maintaining that rule required violence. In Kenya, from 1952 to 1959 British troops brutally put down the Mau Mau Uprising, using torture and mass detention to maintain their control. The stories from that war—rape, castration, thousands killed—are horrific. The Queen’s personal responsibility is doubtful (the monarch has only ceremonial powers) but she was the British Empire’s head of state. Is there no moral weight to that job? Does she only receive the cheers, not the jeers?

Next, because of these alleged crimes, Anya went on to hope that when Queen Elizabeth dies her “pain be excruciating.” This wish, that a beloved national icon, a frail woman of 96, should suffer horribly, was jarring to read.

Anya, of course, had no power to make that suffering a reality. She was sending ill wishes, but those do as much harm as thoughts and prayers do good. It was simply a more unpleasant way of emphasizing how much she hated the British. It’s not a crime to wish someone, or a nation, ill.

She also wasn’t attacking a private person, Lizzy on the block. Professor Anya’s target was Elizabeth Alexandra Mary of the House of Windsor, Queen of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the British Dominions, Defender of the Faith, whose face is on banknotes from London to Ottawa.

Legally and socially we give people more leeway to malign political leaders than private individuals and this is a good thing. National leaders—with their power, influence, and privilege—can’t be above criticism, no matter how beloved they are.1 I’m sure there are many Trump voters who think their hero should also be free from condemnation, and maybe even a few Biden fans who think the same about their guy.

The term lèse-majesté (“injured majesty”) stems from the idea that the monarch is supposed to be above criticism. Committing lèse-majesté in an absolute monarchy was treason. Many people are treating Queen Elizabeth as a similarly sacred figure. Thursday’s Twitter was filled with folks saying that they did not want to hear any criticism of the Queen.

Not everyone got the memo, and that’s ok.

Gilbert Gottfried told one of the first 9/11 jokes post-September 11 (at the Hugh Hefner roast). I don’t remember if I appreciated it at the time, but I absolutely do now. He was a brave and beautiful man. I’m less thrilled by Colorado Professor Ward Churchill, who back in 2001 called the 9/11 victims “Little Eichmanns” who deserved to die, but I strongly supported his right to speak and write as he wished.

I have no strong feelings about Queen Elizabeth—just some admiration for her stoic style—and I had no desire to sling any mud in her direction. Nevertheless, I’m happy that other less deferential people—like the entire staff of The Onion—spent the day showing zero respect for Her Majesty. As long as somebody feels free to make fun of the Queen it leaves me room to make fun of Mitch McConnel.

A Twitter friend said that all the gleeful attacks on the Queen had made them despair about humanity. I understand their reaction but I disagree. We need a healthy amount of idol toppling to keep sacred cows from getting too comfortable.

If you’re in favor of freedom of speech that means you are in favor of freedom of speech precisely for views you despise.

— Noam Chomsky

Should Twitter have deleted her tweet? Absolutely not. She threatened nobody, undercut no democratic norms, and didn’t use any of Twitter’s constantly shifting forbidden words. She simply attacked someone a lot of people loved.

I’ve heard many say “I support free speech, but her words were beyond the pale,” however all that means is that they didn’t like her words. If you only want to defend “good” speech, you aren’t defending free speech. To protect free speech we must defend words that seem beyond the pale.

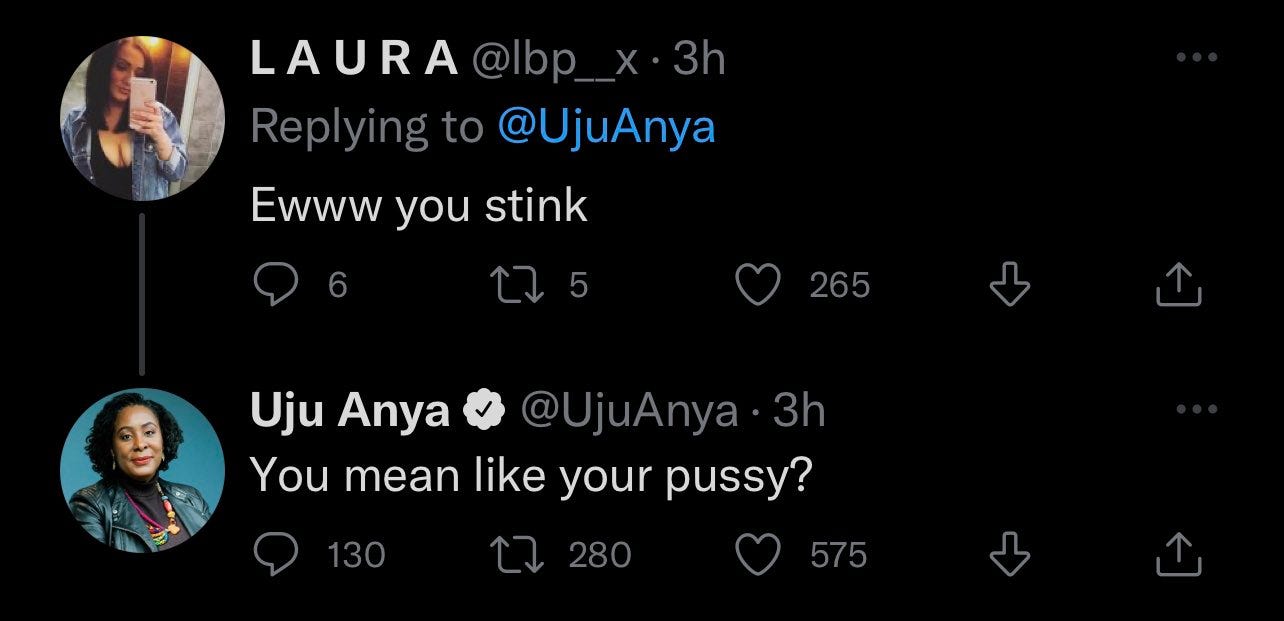

I don’t know Professor Anya, but my impression is not positive. She has a history of nasty tweets. She strikes me as sanctimonious. Last month she was Twitter’s main character when she told us all we needed to be more polite and not ask people where they’re from:

Given her anti-Elizabeth tweets, she seems to have a very unusual definition of “polite.” Still, she has the right to be an obnoxious hypocrite.

My belief in free speech is so profound that I am seldom tempted to deny it to the other fellow. Nor do I make any effort to differentiate between the other fellow right and that other fellow wrong, for I am convinced that free speech is worth nothing unless it includes a full franchise to be foolish and even to be malicious.

— H. L, Mencken My Life as Author and Editor2

We defend even awful speech for the same reason the ACLU defended the right of Nazis to march at Skokie in 1977: so that our own rights are defended. Don’t forget that somebody somewhere already thinks your words are awful. We defend Professor Anya’s right to vilify the Queen because we hope to make sure someone else isn’t fired for praising J. K. Rowling or Nikole Hannah-Jones.

Carnegie Mellon University

CMU was right, of course, not to fire Anya. The right-wingers who rail against cancel culture are being grossly hypocritical in calling for someone to be fired over words on Twitter. Carnegie Mellon’s main fault was in bending too far in the face of public outcry.3

Universities have a special obligation to defend unpopular speech by their professoriate. Part of a professor's job is to push at the boundaries of what is acceptable. There was a time when most right-thinking people agreed that homosexuality was disgusting, a sin, and yet writers and intellectuals pushed against that unjust slander. America used to be under the British monarchy but angry intellectuals attacked the idea (Tom Paine called George III “the Royal Brute of Great Britain”) until revolution brought the redcoats down.

Imagine if Carnegie Mellon had issued this statement:

Free expression is core to the mission of higher education.

We have no other comment.

Some have suggested CMU should have said nothing at all, because her words needed no defending, and while I think this is a very reasonable position, some words in support of free expression were worth making.

What CMU did instead, however, was sadly unimpressive. It’s good that they said “free expression is core to the mission of higher education,” but all their words before and after that statement undercut the message. It’d be like a friend telling me “Carl, I have your back!” and I look over to see him 30 feet away and edging towards the door. Carnegie Mellon gave as weak sauce a defense as I can imagine.

Another argument I’ve seen on Twitter is that CMU had a right and an obligation to distance itself from Anya’s words.

Firing her would be wrong, but they aren't doing that. All they are saying is that they strongly disagree with her views. If they didn't say that, some might be left with the impression that she is representing her employer.

Universities exist to teach students and advance our understanding of the world, they are not there to make their position clear on issues of the day. I suspect that ninety percent of my campus supported Joe Biden in 20204 but my school didn’t issue an official endorsement (I know of no college that did). It’s bad enough that your local bakery feels obligated to put up placards listing all the issues it supports (so you can be sure you are purchasing virtuous crumb cake), our universities should at least maintain the pretense of ideological neutrality.

People have opinions, universities have goals and missions.

As for Carnegie Mellon distancing itself from Anya’s words for PR reasons, that was completely unnecessary. Few people truly think that the University would be endorsing her tweets by not condemning them (despite what Tucker Carlson might say on the air).

Now am I arguing that all speech from an academic must be allowed? No. All rights have limitations. I can imagine Professor Anya crossing lines that would make it reasonable for her school to discipline or even fire her. A continued volley of such tweets directed at a wider swathe of people, tweets that targeted private individuals, tweets that crossed over into actual libel, tweets that advocated horrific crimes. They would have to be pretty extreme, though, and I don’t think it’s likely that she’ll go there.

Although, who knows, maybe she will.

In 1995, eternal troublemaker Christopher Hitchens came out with The Missionary Position: Mother Teresa in Theory and Practice, a book attacking the beloved Catholic nun. He was widely criticized (how dare he?!?) but made a good case that her saintly reputation hid some shady behavior.

Originally, I wanted to use this perfect Menken quote (suggested by a Twitter follower):

”The trouble with fighting for human freedom is that one spends most of one’s time defending scoundrels. For it is against scoundrels that oppressive laws are first aimed, and oppression must be stopped at the beginning if it is to be stopped at all.”

But I couldn’t nail down the source. It’s attributed to Mencken by many folks, from Alan Dershowitz to Slate Star Codex but none of them gives an original source. They just said “by H.L. Mencken” with nary a source nor qualm, but that’s not how I roll! (But I still stuck it in this footnote!)

Too many people who rail against cancel culture will turn on a dime and demand the firing of someone they consider in the wrong. It’s never hypocrisy when we do it.

The other ten percent thought he was too conservative.

How are you better on Substack than Twitter? That's just unfair. This is one of the more enjoyable defenses of the concept of free speech I've read in a while.

While I agree with you that CMU should defend free speech, and it shouldn't make a difference if the speech is vile, I don't think the CMU statement is weak sauce. It shows that they'll defend free speech even when it's nasty.

Emphasising the nastiness of the free speech you'll defend can make the defense stronger. When the ACLU defended the Nazis in the Skokie case, they issued a pamphlet: "Why the American Civil Liberties Union Defends Free Speech for Racists and Totalitarians". By showing that they'll even defend racists, they showed that they took free speech seriously.

The abstract statement "Free expression is core to the mission of higher education. We have no other comment." is not that powerful. I imagine they also think social justice is core to the mission of higher education. How would CMU respond if those core mission statements collide? You need to show that free expression trumps social justice.