As with so damn much these days, it started with a tweet from Elon Musk.

Because the man is worth 99,999 billion and everyone watches him 24/7, pandemonium ensued.

A few people noted that the top quote has some issues. One was me.

I was far from alone. I’m always thrilled when Fake History Hunter steps up to the plate.

And there were Musk fans who liked the quote because of its antisemitic connections. (The “Committee of 300,” is an antisemitic conspiracy theory—dating back to Weimar Germany—that claims 300 Jewish men run the world.)

What happened?

A few things need to be clarified.

First, Elon Musk is not antisemitic. It’s quite possible he didn’t even know the history of that particular quote.

Second—and here I messed up—, these weren’t even Strom’s original words. Back in 1993, Strom said in a radio broadcast:

To determine the true rulers of any society, all you must do is ask yourself this question: Who is it that I am not permitted to criticize?

At some point, some unknown person modified the quote and attached Voltaire’s name to it because that’s a lot more appealing than a neo-Nazi moniker.

Third, and this is key, Musk was NOT endorsing the fake Voltaire quote. He tweeted the image because of the satirical comment at the bottom, “We need to rise up against children with leukemia.” That comment is making fun of his quote. We’d rightfully suffer opprobrium if we criticized kids with cancer, but this does not mean they rule over us. The comment is poking a big hole in the logic of the Kevin Strom quote. The comment is Musk’s punchline.

If this isn’t clear, Musk makes it explicit a day later in responding to a Forbes tweet and article that unfairly targeted Musk’s original tweet.

Fourth, and to be fair to Musk fans, many of them did see the leukemia comment and did understand that Musk was ridiculing the “Voltaire” quote.

Ok, so Musk wasn’t being antisemitic. He thought the comment (leukemia) was a good zinger on a simplistic idea—the “Voltaire” quote—and tossed it off without thinking twice.

But the quote Musk was ridiculing is still misattributed, and it’s from a neo-Nazi, and I see those facts as problems.

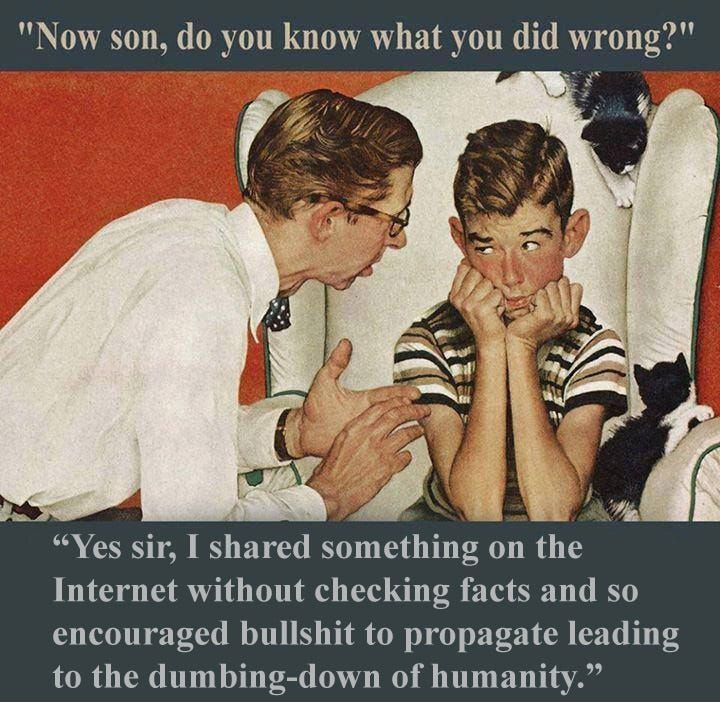

We should get quotes right. Once we start getting sloppy about little things, we’ll do the same about bigger stuff. Even though Musk’s tweet was focused on poking fun at the quote, not spreading false information, he still appeared to be poking fun at Voltaire’s ideas, and the tweet inevitably had the result of convincing scads of idiots that Voltaire really said those words. If you put information into the universe, you have a responsibility to make sure it’s accurate.

Is it evil?

Now the trickier question is should you use the quote at all, given its unsavory provenance?

Or, as my friend Angel Eduardo put it:

Ok, I’m going to hit this from a few directions.

First, provenance seems to matter when the source is someone we admire. Twitter is filled with quotes from Martin Luther King, Abraham Lincoln, and John Stuart Mill. We mention their names with their quotes because we understand that a quote from King or Lincoln has added weight. It’s why the fake quote credits Voltaire. The name of an Enlightenment philosopher gives Strom’s words a sense of gravitas they wouldn’t have had otherwise.

If a man’s name gives extra weight to his words, why wouldn’t a different man’s name tarnish a different set of words?

Now I wouldn’t take this idea too far. We shouldn’t be checking every artist and writer and digging up all their dirty laundry. We all have warts. Picasso was a jerk. Hemingway too. But the Nazis are another level of evil. Theirs was an ideology of brutal conquest and genocide. This goes light-years beyond abusive husband territory. I’m against paying any attention to artists’ lives (especially the dead ones), but I think Nazis belong in a special category. In my world, they get their own rules.

If we take the quote, “To learn who rules over you, simply find out who you are not allowed to criticize,” and add proper attribution, what happens? Two seconds of research will tell your reader that Strom is a neo-Nazi Holocaust denier. We’ll realize right away that he was referring to Jewish people ruling the world. That knowledge can’t help but influence what people think of the quote.

Words aren’t isolated nuggets of soulless information. They have context. We speak of connotation as well as denotation.

a feeling or idea that is suggested by a particular word although it need not be a part of the word's meaning, or something suggested by an object or situation

What feeling are you communicating when you quote a neo-Nazi saying a racist thing? You can’t tell people not to think about his past; humans don’t work that way. If I meet a guy who’s dropping Hitler bon mots into every conversation, I’ll start giving the guy some serious side-eye. If he quotes a Nazi on how “work will set you free,” I’m going to know he’s using the quote emblazoned at the entrance to the Auschwitz death camp. (“Arbeit macht frei.”)

And what was Strom trying to communicate with his words? When he spoke of “the true rulers of any society,” he was speaking of Jewish people, pushing the conspiratorial theory that Jewish bankers, politicians, etc., control everything, pulling the strings that make government and business dance. Look at the image next to the “Voltaire” quote. That chubby hand pushing down is a racist caricature of a Jewish hand. Notice the faint glimmer around the diamond ring on one finger, symbolizing Jewish wealth. Once you know that meaning, you can’t unknow it. It’s there, part of the multiple meanings that any set of words carries.

We are free to use Strom’s words, of course, but we have to be aware that they will bring all that baggage with them.

There are other problems with using such a man’s words. We may attract people who need no encouragement. Like the special person below who was in the responses to my tweet.

I had quite a few special people telling me the Holocaust was a “fabrication.”

You can plead innocence after using a Nazi quote. “That’s not what I meant!” Yes, I believe you, but that’s what some people will hear. You are not in sole charge of what the words you use mean. They carry a suitcase full of ideas. If I say “Bob is well-meaning,” it doesn’t just translate as “a guy with good intentions”; it has the connotation of “a guy who tries but screws up in some way.” You can still use that phrasing—I’m not censoring you!—but don’t be surprised if Bob’s feelings are hurt when he hears about your “compliment.”

What if the Nazi quote is true? Should the source stop us from using it?

If a bigot says to me, "The sun is shining." If the sun is shining, I say, "Yes the sun is shining," because I want to tell the truth.

— Bayard Rustin

But Rustin isn’t telling us we need to quote bigots, just acknowledge when they’re right about reality. What deep truth are you missing out on if you don’t use Strom’s exact words? The man was not a poet. His original phrasing was clunky, and the rephrasing is hardly an amazing piece of art. Not using those exact words is not a great loss to humanity.

And the argument made by the words? It’s weak. Sure, there’s a certain appeal. (I called it “cool” in my tweet.) Think of all the things you “can’t say” today; it shows you were power lies! Except, does it? Yes, criticizing the Black Lives Matter movement, for example, will get you a dumpster full of grief if you live in certain liberal spaces. So? Does that mean black people run America? Hardly. And BLM gets plenty of criticism from voices on the right, and some on the left as well (Sean Kevin Campbell has done some great reporting on corruption at BLM for New York Magazine). The real powers are the moneyed classes, guys like Elon Musk, and you can criticize those guys all you want. They don’t care.

Now let me turn on my own arguments and admit there are some risks to this way of seeing things. We live in a time when people are far too worried about offensive words. Professors have gotten in trouble for using a word in Mandarin (“nei-ge”) that sounds like the n-word. Students get upset (and professors fired) if they see a picture of Mohammed in an art history class. Or there’s a recent trend of thinking that calling someone “homeless” is offensive, so instead, you should say, “people experiencing homelessness.” (Which does nothing to reduce the number of homeless people.)

It’s reasonable to fear that suggesting people not quote a neo-Nazi feeds the same kind of oversensitivity, but I think it’s ok to make a few special exceptions without worrying overmuch about slippery slopes. Nazis are in a class by themselves. Following a “try to avoid using Nazi quotes” guideline doesn’t seem likely to bleed over into everything else.

It is admittedly a difficult area to navigate. Driving a VW bug doesn't make one antiSemitic, even though the car was first designed under the auspices of the Nazis. At what point was it no longer a Nazi car but just a car? At what point is a quote no longer a Nazi quote but just a quote?

Nice to see that you remain impervious to audience capture 🙌